Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

The following blog post was originally written for the Treasury Historical Association and was shared in their August 2018 newsletter. It is based on a lecture given to the Treasury Historical Association in the Cash Room of the Treasury Building on May 16, 2018.

Thanks to numerous biographies and a wildly popular Broadway musical, Alexander Hamilton’s many contributions to this country—artillery captain in the early days of the American Revolution, Washington’s aide-de-camp, member of the Constitutional Convention, primary author of the Federalist Papers, first Treasury Secretary, and much more—have become well known, as has his love life and his famous duel with Aaron Burr. However, Hamilton’s childhood in the Caribbean has been largely neglected and deserves more attention because these formative years in the West Indies were essential to his development into a future Founding Father. As a youth on St. Croix, Alexander Hamilton worked as a clerk for a growing mercantile company and at one point managed the entire firm. The skills and relationships that Hamilton acquired during this “most useful part of his education” would be employed with great success as he helped shape the new nation.

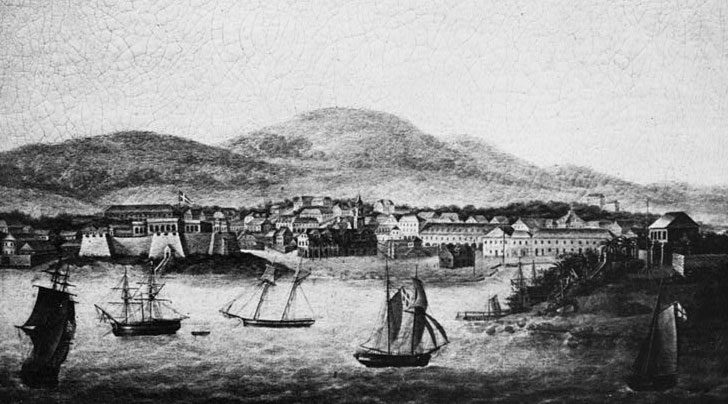

Alexander Hamilton arrived with his parents and brother on St. Croix in 1765. The following year, the 9-year-old Alexander went to work for the mercantile company of Beekman & Cruger. David Beekman and Nicholas Cruger belonged to two of New York’s most prominent and influential mercantile families. David Beekman soon left the business to Nicholas Cruger, who would occasionally partner with Cornelius Kortright, another son of a prominent New York mercantile family.

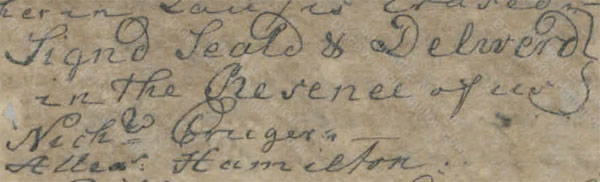

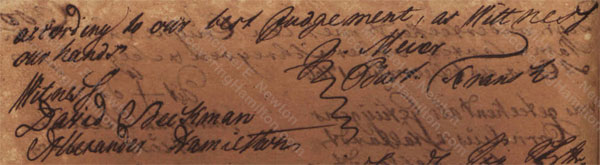

In April 1767 and again in August, in the earliest known Hamilton documents, young Alexander, just ten years old, was acting as a witness to legal documents for his bosses. Hamilton’s employers thus recognized his maturity and accorded him a level of responsibility almost incredible for one so young.

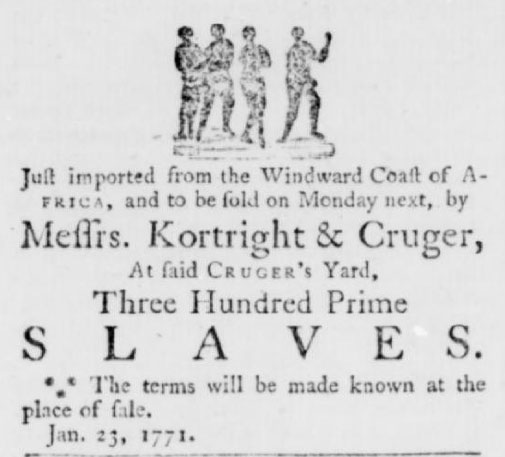

Beekman, Cruger, and Kortright imported provisions for the sugar-producing plantations and in turn exported sugar, molasses, rum, and cotton. They also imported slaves to work on the plantations. As an employee, Hamilton would have been there when these slaves were unloaded from their ship and groomed for sale. He also would have attended the auction, where he probably recorded the sales information. Hamilton would surely recall the plight of these unfortunate men, women, and children when he used his influence to support the manumission of slaves, the education of free blacks, and more rights for these oppressed people.

Business was conducted in at least a dozen currencies. This required skilled clerks to calculate and record everything properly. Business was also conducted in many languages, primarily English but Danish was the official language used in the courts and government. And they traded with others from Dutch, Spanish, and French islands, some of whom did not know English. Knowledge of a foreign language was therefore very helpful. Alexander Hamilton was fluent in French, whereas Nicholas Cruger did not “so well understand the French language, from want of practice.” The records seem to indicate that Hamilton was in charge of translating the French letters coming into the office.

As a clerk, Hamilton spent most of his days sitting at a desk minding accounts and writing letters for his bosses. By November 1769, Alexander Hamilton complained to a friend, “I contemn [despise] the grov’ling and condition of a clerk or the like to which my Fortune etc. condemns me, and would willingly risk my life though not my character to exalt my station.” This shows that Hamilton was a clerk for the company but that he no longer enjoyed such tedious work.

When a ship with cargo arrived, Hamilton probably headed to the docks with one of his bosses to help supervise the unloading of cargo, inspect the merchandise, and log the inventory. Perhaps by the time he complained about his job as a clerk, he was already performing these tasks on his own. Although far from glamorous, this work placed Hamilton at the economic center of the island, where he would meet planters, ship captains, other merchants, and government officials.

In October 1771, Nicholas Cruger, now operating alone, departed St. Croix for New York to recover from a “very ill state of health.” Both Beekman and Kortright were on St. Croix, but Cruger put 14-year-old Hamilton in charge of his company.

Over the next five months, Alexander Hamilton probably spent the largest portion of his time managing the actual import and export of goods. Shortly after taking over, Hamilton welcomed a new vessel, the Thunderbolt, owned by Nicholas Cruger along with his brother and brother-in-law, and informed his boss that it was “a fine vessel indeed, but I fear not so swift as she ought to be.” Within 48 hours, Hamilton had supervised the unloading of Indian meal, staves, apples, lumber, bread, and onions, paid the duties to the customs officials, and prepared the Thunderbolt for departure to Curacao and the Spanish Main. Another time, Hamilton supervised the nearly simultaneous arrival of four ships delivering cargo for Nicholas Cruger, two of which “arrived within a few hours of each other.” Hamilton quickly turned around three of the ships, but the fourth had its cargo “stowed very inconveniently” and “Hickledy-pickledy” (possibly a technical mercantile term). “Nothing was neglected on” Hamilton’s “part to give him the utmost dispatch,” and the ship was “ready to sail seven days after his arrival.” Not bad for a 14-year old.

After unloading these ships, Hamilton had inventory to manage. One time, he received apples that “were in every respect very indifferent.” Another time, he unloaded 290 barrels of “Philadelphia flour” that was “really very bad, being of a most swarthy complexion,” which “upon opening” was discovered to have “a kind of worm very common in flour about the surface, which is an indication of age.” Hamilton decided to offer these goods to buyers at a discount in order to move his merchandise. On another occasion, when the Thunderbolt returned from Curacao and the Spanish Main, Hamilton found himself with 41 mules that were mere “skeletons” (seven mules had died on the voyage). Rather than sell low, Hamilton sent the mules to pasture. In the end, Hamilton spent a mere 2 pieces of eight for one month of pasturage per mule and sold the recovered mules for 30 pieces more than had been initially offered. Clearly this kid knew what he was doing!

In addition to managing ships and merchants, Hamilton had to supervise numerous people, most notably the ship captains who sailed for him and his boss. After the Thunderbolt’s dismal voyage, Hamilton instructed the captain to “reflect continually on the unfortunate voyage you have just made and endeavour to make up for the considerable loss therefrom accruing to your owners.” Hamilton also warned their connection in Curacao “that you cannot be too particular in your instructions to him. I think he seems rather to want experience in such voyages.” But to Nicholas Cruger, Hamilton defended the ship captain, who “seemed to be much concerned at his ill luck.” Hamilton argued that the “mules were pretty well chosen & had been once a good parcel” and the captain “had done all in his power to make the voyage successful” but “no man can command the winds.” Hamilton’s management of the situation worked like a charm. The Thunderbolt returned from its next voyage with a “cargo [of] mules in good order.” Hamilton sold the mules for good prices, “which makes some demands for her first very bad cargo.”

While all this was going on, Hamilton made the executive decision to fire one of the firm’s two attorneys and transfer all the legal work to the other. Upon his return, Cruger approved of Hamilton’s action and was “confident” that this lawyer had been “very negligent” and “trifled away a good deal of money to no purpose.”

Hamilton also visited or wrote to various people to collect debts owed to Nicholas Cruger. Hamilton pressed one person to provide “an immediate answer” because “the gentlemen” to whom he owed money “expect a punctual compliance with the tenor of the bill. . . . I hope it may be in your power to give them satisfaction.” Hamilton informed his boss, “Believe me Sir I dun as hard as is proper.”

Alexander Hamilton also spent considerable time managing the company store in the heart of Christiansted, St. Croix, from where he sold goods to households, plantations, and shopkeepers. One shopkeeper who purchased goods from Beekman & Cruger back in 1767, when Hamilton was already working there, was none other than Hamilton’s mother.

With this profusion of commercial activity, Hamilton had to enter each and every transaction into the company’s account books. Every shipment of cargo required meticulous record keeping. Hamilton had to allocate the profits and expenses of each voyage to the various partners who participated or had cargo assigned to the ship. The company conducted transactions in Danish West Indian rigsdalers, reals, pieces of eight, British pounds, and the currencies of various North American and West Indian colonies, all of which had to be converted back and forth in letters, account books, and payments. This required a good head for math and plenty of training, which Hamilton must have had because he was not shy about correcting the accounting errors of Cruger’s business associates.

During his management of the company, Hamilton did business or corresponded with people in New York, Philadelphia, Bristol, Curacao, the Spanish Main, St. Eustatius, St. Kitts, and St. Thomas. And shortly after his return, Nicholas Cruger was corresponding with a merchant in Connecticut, one Benedict Arnold, and his father-in-law, Samuel Mansfield. Years before they fought together and then against each other in the American Revolution, Hamilton surely was involved in unloading and selling Arnold’s cargo and shipping him rum and other freight on the return voyage.

When Hamilton sent the Thunderbolt to the Spanish Main, he was especially concerned with the Guarda Costa, who were “said to swarm upon the coast.” The Guarda Costa were the Spanish Coast Guard, but they often acted more like pirates, confiscating foreign ships on flimsy grounds. Accordingly, Hamilton instructed the ship’s captain to arm himself with cannons and told their Curacao correspondent to help him do so. Hamilton was not pleased when they neglected “to furnish the sloop with a few guns,” forcing the ship to go “entirely defenceless to the Main.”

Tax evasion is a practice as old as taxes themselves, and there are records, which are found in Hamilton’s hand, of Nicholas Cruger performing this deception. In one instance, Cruger instructed his partners in New York to have the “clayed [refined] sugars . . . entered paying the same duty as muscovado [unrefined sugar]” and “carted up immediately for fear of discovery,” thereby evading the higher tax rates on refined sugar. Another time, to avoid the hefty twenty-five percent duty, Cruger asked that the captain see him “before he enters” so he could “enter it as Corn Meal and give the waiter a fee [i.e., a bribe].” Cruger also requested “20 or 30 barrels [of] pork” and asked the supplier to give “the Captain the same caution as above.” Copying this letter, perhaps writing the original as well, possibly being the one sent to bribe the port official, and perhaps doing likewise during his management of the company, Hamilton at this early age learned all about smuggling and tax evasion, something that he’d remember when he started the U.S. Revenue-Marine in 1790, which later became the Revenue Cutter Service and then the Coast Guard.

When Nicholas Cruger returned in March 1772, he praised Hamilton for a job well done. He even stated that he wished he had “stayed a few months longer” in New York to further recover his health, assured that Hamilton would have continued his superb management of the company.

Working for Nicholas Cruger for about 6 years and managing the company for nearly 5 months, Hamilton gained knowledge and skill in accounting, management, finance, trade, credit, economics, and even geopolitics. In managing the company and working with other merchants, ship captains, customs officials, plantation owners, and retail customers, Hamilton developed his talents as an administrator, showing a remarkable ability to instruct older and more experienced men. Hamilton learned the ins and outs of international commerce, foreign exchange, and European mercantilism. In dealing with different nationalities, languages, and currencies, Hamilton recognized the value of standards. With the constant threats of piracy and war, Hamilton gained first-hand experience in defensive preparedness, the value of a navy, and the costs and benefits of maritime insurance. Hamilton would use all these acquired skills and experiences later when he became the Secretary of the Treasury.

Alexander Hamilton’s son summed it up when he wrote, “This occupation was the source of great and lasting benefit to him; he felt himself amply rewarded for his labours by the method and facility which it imparted to him; and amid his various engagements in after years adverted to it as the most useful part of his education.” It was this youthful education in a far-off land that prepared Alexander Hamilton for the far greater deeds he would accomplish as a Founder of the United States.

Copyright

© Posted on September 27, 2018, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

Bravo! Great summary of his early career. (And really: how many 9- to 14-year-olds today have a career?)

Thanks Dianne.

I never tire of reading about Alexander Hamilton and thank you for this post. I am currently reading your, “Alexander Hamilton, The Formative Years” and thoroughly enjoying it, even the first two chapters. Thank you again.

Thank you. Glad you are enjoying the book and the blog.