Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

In last week’s blog post, we saw how a man named William Hendrie from St. Kitts moved to St. Croix and lived there for a couple of years before passing away. We saw how this William Hendrie interacted with Mary Faucett (Alexander Hamilton’s grandmother) and probably with all the Lyttons, Faucetts, and Laviens, who lived nearby. We also saw how he had a son named James Hendrie, who in 1749 was trading with St. Croix but apparently not living there.

James Hendrie on St. Croix

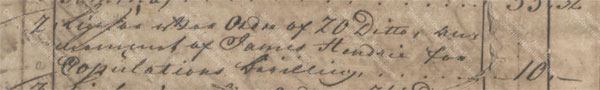

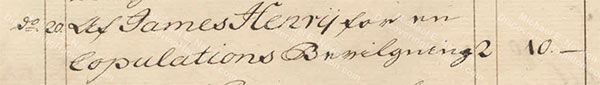

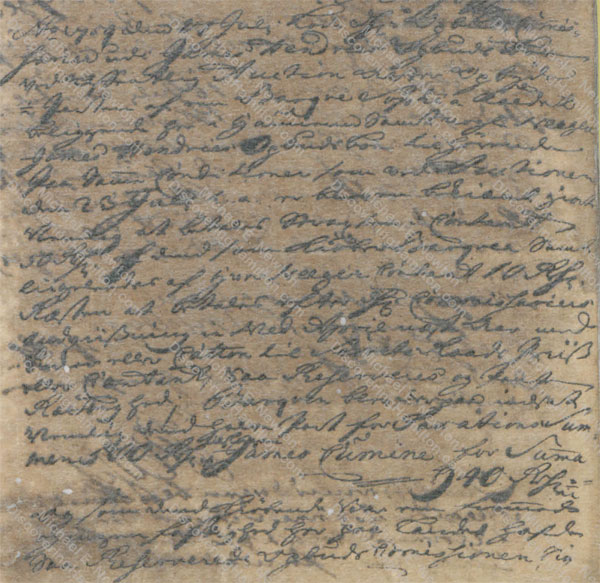

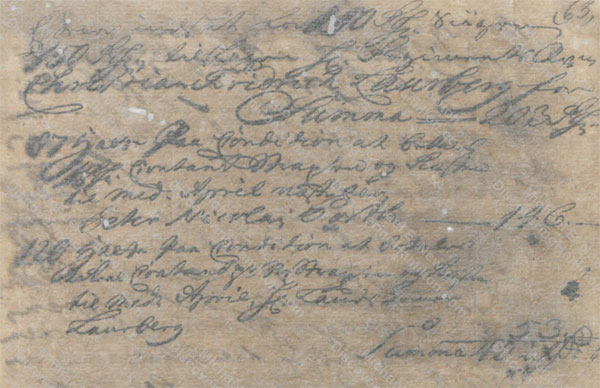

The earliest record of James Hendrie on St. Croix that I have found is an entry, actually two of them, dated March 20, 1758, showing his payment of 10 rigsdalers for his marriage license. Unfortunately, the name of his bride is not given.

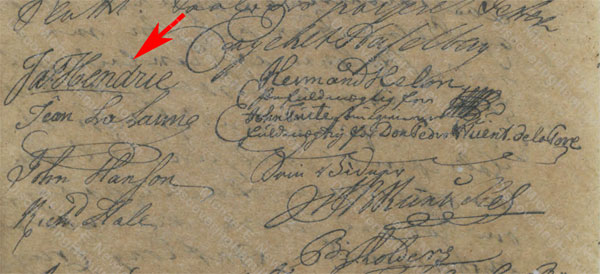

Three months later, in June 1758, James Hendrie is found again in the St. Croix records, this time signing Christiansted’s bailiff register alongside a number of others.

Surely James Hendrie appears in other St. Croix records from this time, but it is noteworthy that no record of him on this island prior to his marriage in March 1758 has yet to be found. One assumes that he came to St. Croix around this time, from where, however, remains a mystery.

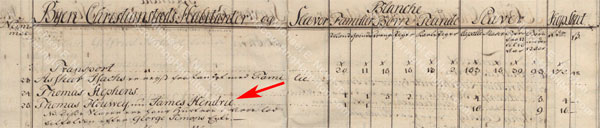

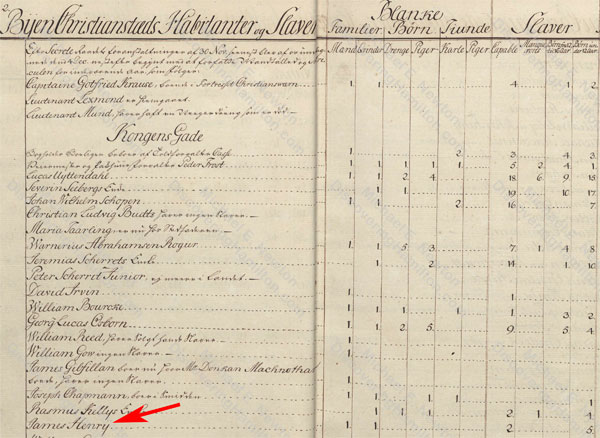

James Hendrie does not appear in St. Croix’s matrikels (the annual property, tax, census register) prior to his wedding, but in the matrikel of 1758 he is listed as living on Kongens Gade (King’s Street) in Christiansted with his wife and 25 slaves, though it is not clear how many if any of these slaves were owned by him.[1]

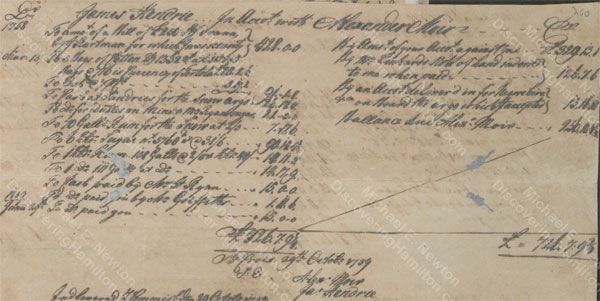

According to an account statement between James Hendrie and Alexander Moir (yes, the same man from whom James Hamilton would later collect a debt), James Hendrie appears to have been acting as a merchant at this time, exporting cotton, rum, sugar, and other goods.

James Hendrie Summoned to Testify as a Witness in Lavien Divorce

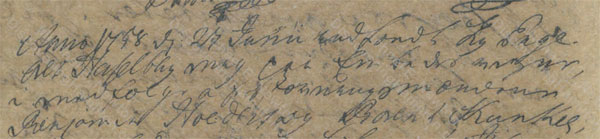

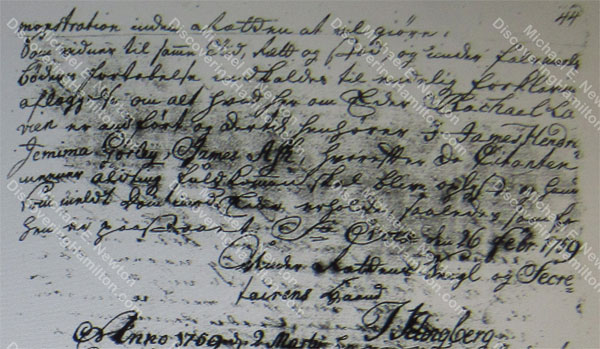

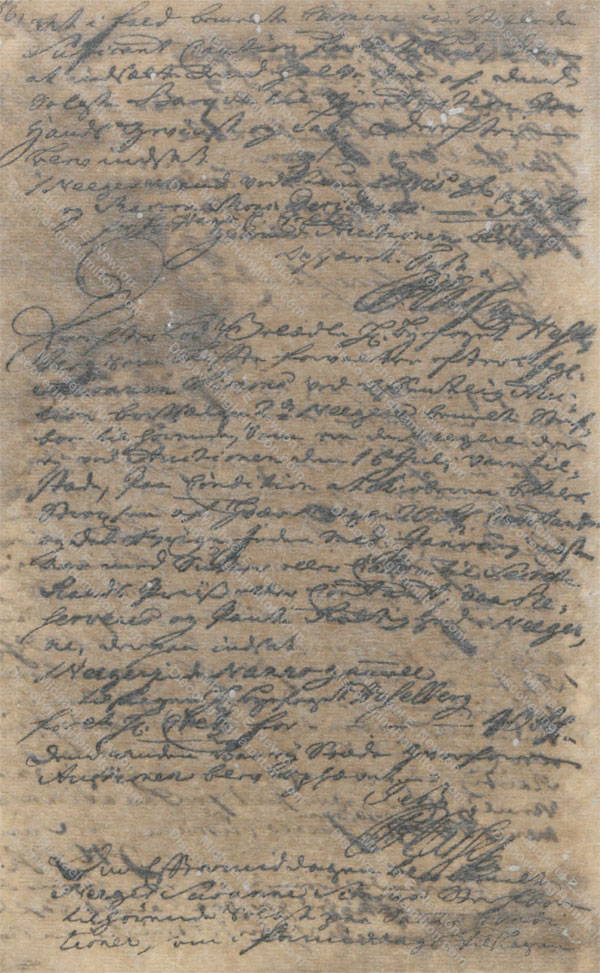

In February 1759, James Hendrie was summoned to testify as a witness in the divorce of John Michael Lavien and Rachel Faucett.

It is not clear what James Hendrie knew that would be worthy of the court’s attention. Although James Hendrie’s father William Hendrie probably knew the Lyttons, Laviens, and Faucetts, and in fact paid Mary Faucett to do some sewing, there is no evidence that James Hendrie knew any of these people. It also appears that James Hendrie was not on St. Croix back in 1749 when Rachel’s affair with Johan Cronenberg took place. More likely, James Hendrie had lived on St. Kitts, from whence his father had come, until he arrived on St. Croix around early 1758. One can thus assume based on his being summoned as a witness that James Hendrie knew James Hamilton and Rachel Faucett on St. Kitts, or at least knew of them. He thus would have been summoned to testify about Rachel’s “illegal” relationship with James Hamilton on that island.

As with Jemima Faucett Iles Gurley and James Ash, no record has been found of James Hendrie’s testimony as a witness. In fact, there is no record regarding whether he testified or appeared before the court.

Accordingly, we do not know if James Hendrie knew anything above and beyond what was already in the court record or which side he would have taken in this matter, but one assumes, as mentioned above, that he was summoned to report on the relationship of James Hamilton and Rachel Faucett on St. Kitts.

James Hendrie Goes Bankrupt

On July 27, 1759, and again on August 10, the government auctioned off some of James Hendrie’s property. Apparently, James Hendrie was having trouble managing his debts and his property was being seized and sold to pay back his creditors.

Despite these apparent financial troubles, James Hendrie is found in the 1759 matrikel, still living on Kongens Gade (King’s Street) in Christiansted, with his wife and seven slaves.

This would be the last time that James Hendrie appeared in the island’s matrikels.

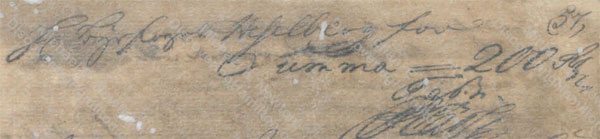

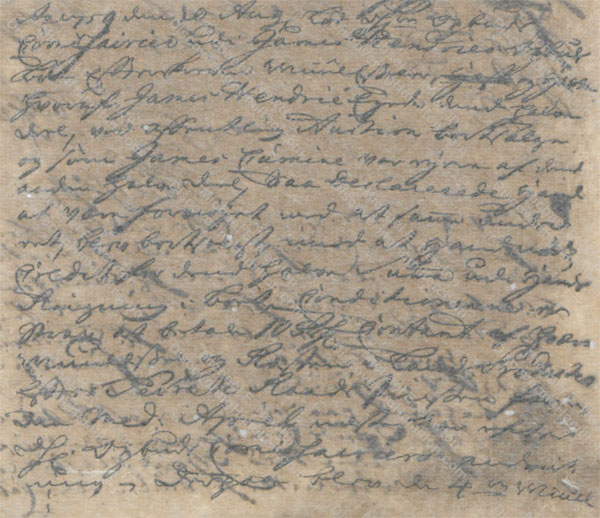

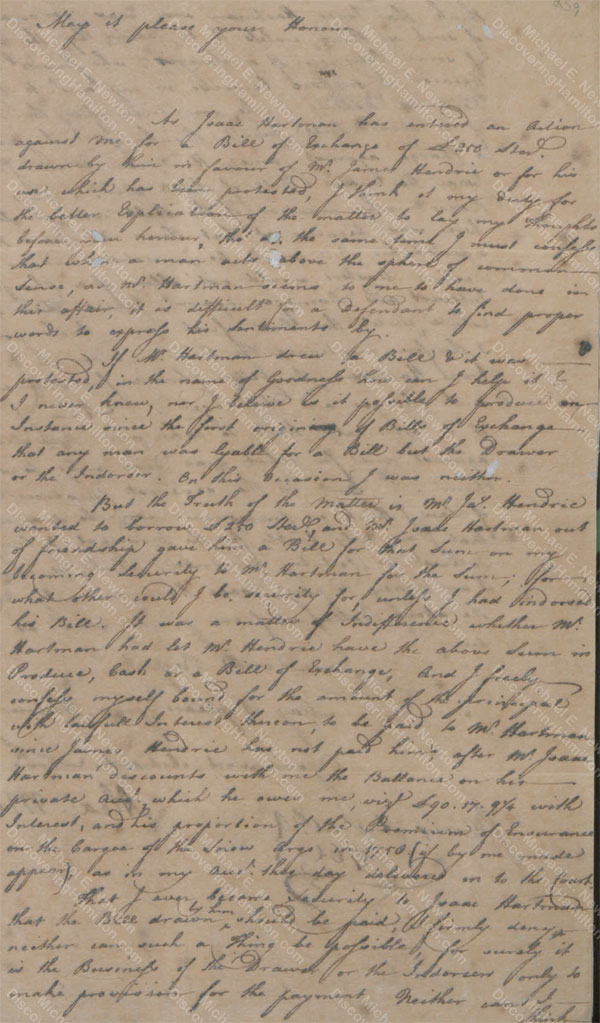

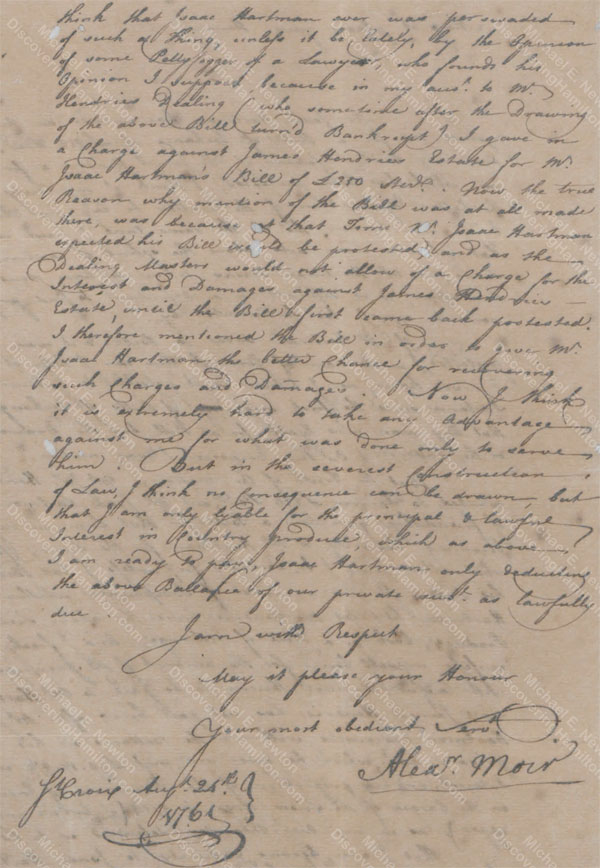

According to a statement by Alexander Moir dated August 24, 1761, James Hendrie owed an Isaac Hartman £250 sterling plus interest but had “turn’d bankrupt” since borrowing this sum and Moir “gave in a charge against James Hendrie’s estate” for the £250 sterling.

When exactly James Hendrie “turn’d bankrupt” is not mentioned, but it presumably was sometime in 1760 because he still owned seven slaves at the end of 1759 but is no longer listed in the matrikel at the end of 1760, meaning that he no longer owned any taxable property, i.e., land or slaves.

No longer appearing in the matrikels, one would assume that James Hendrie fled the island to avoid imprisonment for outstanding debts. However, it is possible that he stayed on St. Croix but was not listed in the matrikels because he no longer owned any land or slaves on the island and therefore did not have to pay any taxes. It is noteworthy that Alexander Moir mentioned Hendrie having “turn’d bankrupt” as a reason for his not paying his debt but did not mention him leaving the island. One would therefore assume that he stayed on St. Croix even though he does not appear in the matrikels.[2]

To be continued…

Endnotes

[1] Translated, the matrikel reads: “Thomas Houwey, now James Hendrie. N.B. These slaves are [with] Hans Gustman in behalf [of the] share inherited by George Simons widow.” This would imply that all 25 slaves belonged to Simons’s widow and were being held by Gustman. However, the previous year, Thomas Houwey is listed at this same location with seven slaves. The following year, James Hendrie, still on King’s Street and presumably at this same location (that matrikel does not number the properties), owned seven slaves. Accordingly, one might think that seven of these slaves may have belonged to Hendrie.

[2] The matrikels at this time were primarily but not exclusively records of taxable property, i.e., land and slaves, and the taxes owed on them. They also counted the number of white people, but did not list them all. People working as servants, clerks, and plantation managers would be counted in a column for white servants and would not be named unless they also owned landed property or slaves, upon which taxes had to be paid.

Copyright

© Posted on October 15, 2018, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.