Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

© Posted on April 9, 2018, by Michael E. Newton.

In 1685, John Hamilton of Grange acquired a large estate in Stevenston Parish, Ayrshire County, Scotland. He removed from the Grange at Kilmarnock and took up residence in Kerelaw Castle, which had been built on the property centuries earlier and sat just north of the town of Stevenston. It was here that Alexander Hamilton’s grandparents, Alexander Hamilton and Elizabeth Pollock, lived and raised their large family, which included Alexander Hamilton’s father, James Hamilton.

Descriptions of Kerelaw Castle and its Ivy

In his “recollections” published in 1869, Alexander Hamilton’s son, James Alexander Hamilton, wrote of his visit to Kerelaw Castle in 1837:

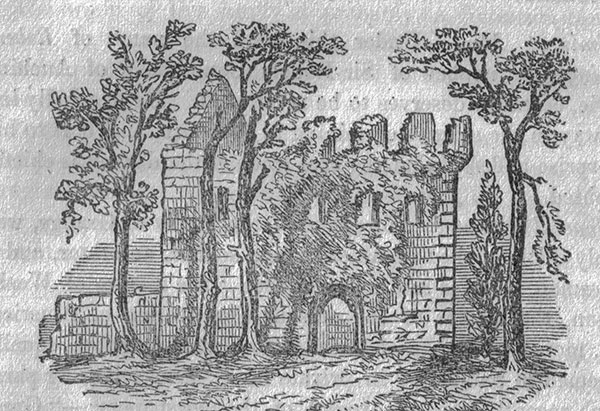

My most interesting visit was to Grange, in Ayrshire, the residence of Alexander Hamilton, who was a cousin of my father. My grandfather, James Hamilton, had lived on this place—not in the house the Laird now occupied, but in a large stone house of which the ruins still remained, covered with ivy.[1]

Ever since, Alexander Hamilton biographers have written about Kerelaw Castle and its ivy-covered walls.[2] Alexander Hamilton’s grandson, Allan McLane Hamilton, quoting a book from 1876, wrote of “the ivy-mantled ruins of Kerilaw Castle.”[3] James T. Flexner described James Hamilton’s “childhood home” as “partly habitable, partly a ruin,” with “thick masonry, almost hidden by ancient ivy.”[4] Willard Sterne Randall likewise wrote, “Alexander Hamilton’s father grew up in this romantic ruin, its thick stone walls, covered with ivy.”[5] And Ron Chernow stated, “In 1685, the family took possession of ivy-covered Kerelaw Castle.”[6]

Contemporary Descriptions

Despite the oft-repeated statement, either implicitly or explicitly, that Kerelaw Castle had ivy-covered walls when the Hamiltons purchased it in 1685 and when James Hamilton lived there from about 1721 to perhaps 1737, no source from those periods has been found describing the ivy. Timothy Pont described the castle in the early 1600s as:

Karylaw castell, or Steuinstoune [Stevenston] castell, a faire stronge bulding, belonging to the earls of Glencairne, quho [who] had the said castell, barroney, parisch, and lordschipe by the mariage of the Douglass, heritrix therof. It belonged in anno 1191 to the Lockarts.[7]

An 1820 “Topographical Description of Ayrshire,” also failed to mention Kerelaw’s ivy-covered walls,[8] but this work does not describe any part of the already ruined building, so this omission does not allow us to draw a conclusion regarding whether the ivy existed at this time.

Thus, the earliest source that has been found regarding Kerelaw’s ivy-covered walls, at least in a Hamilton-related book, appears to be James A. Hamilton’s 1837 visit to the ruined building.

So, did Kerelaw Castle have ivy-covered walls when the Hamiltons purchased it in 1685? Did James Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s father, grow up inside thick walls covered by ivy? Or did the ivy sprout up and begin to cover the castle walls at a later date?

Planting the Ivy

In 1887, writing about the birds of Ayrshire, David Landborough, a resident of the area, shared this interesting story:

My memories of Stevenston parish carry me back a few years farther, and I remember that I then knew of only one place where the Starling was to be seen. This was at the striking old ivy-clad castle of Kerelaw, interesting to Glasgow people as associated with the distinguished divine, Dr. Love, of Anderston Church, who, in the year 1775 lived in the castle as tutor to the Hamilton family. It continued to be occupied by this family till about the year 1787, when a new mansion was built and the old castle planted with ivy. The ivy became most luxuriant; and here it was that as a boy I was wont to listen to the pleasing and not unmusical chattering, and clear whistling of the Starling. Soon afterwards the bird had greatly increased and become so tame that it was only necessary to erect a suitable box for its selection as nesting quarters. These boxes, placed on the tops of chimneys, trees, or tall poles, were a source of much pleasure to almost all the boys in the neighbourhood.[9]

It is now clear that it was not until “a new mansion was built” and Kerelaw abandoned “about the year 1787” that “the old castle [was] planted with ivy.” Thus, despite the assertions of many Hamilton biographers, the walls of Kerelaw Castle were not covered with ivy when the Hamiltons purchased it in 1685 or when James Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s father, grew up there. It was not until many decades later that ivy was planted at the old ruined castle, grew “luxuriant,” and became worthy of mention by Hamilton biographers.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

Endnotes

[1] James A. Hamilton, Reminiscences 302.

[2] Included are just a few examples found in some of the more notable Hamilton biographies. Many others repeat these assertions.

[3] Allan McLane Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton 438–439. The first paragraph quoted by Allan McLane Hamilton appears in the original 1604–1608 text by Timothy Pont, but the second paragraph, which mentions “the ivy-mantled ruins of Kerilaw Castle,” belonged to the “continuations and illustrative notices” added by John Shedden Dobie in 1874.

[4] Flexner, The Young Hamilton 17.

[5] Randall, Alexander Hamilton: A Life 16.

[6] Chernow, Alexander Hamilton 13.

[7] Pont, Topographical Account of the District of Cunningham, Ayrshire 21–22. The additional notes at the end of this published work, written about 1858, also make no mention of the ivy, even though James A. Hamilton had already seen it.

[8] Robertson, Topographical description of Ayrshire 167–168.

[9] Proceedings and Transactions of the Natural History Society of Glasgow, New Series, Volume II 299.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.