Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

Last week we saw how many historians and biographers mistakenly conclude that Alexander Hamilton was “girl crazy and brimming with libido” based on a letter he wrote to Catharine “Kitty” Livingston in April 1777. Proponents of this idea would defend themselves by pointing out that this is not the only story about Hamilton during the American Revolution showing him to be “girl crazy.”

On January 1, 1780, a Captain Smythe wrote:

Mrs. Washington has a mottled tom-cat, (which she calls, in a complimentary way, ‘Hamilton,’) with thirteen yellow rings around his tail, and that his flaunting it suggested to the Congress the adoption of the same number of stripes for the rebel flag.[1]

Repeat and Embellish

This anecdote about Martha Washington naming a tomcat Hamilton has been repeated and embellished in dozens of books and essays. A few examples will demonstrate the evolution of this story:

In 1902, Gertrude Atherton wrote about Hamilton in The Conqueror:

The Lady-in-chief made such a pet of him that he was referred to in the irreverent Tory press as “Mrs. Washington’s Tom-cat.”[2]

Not only did Atherton report the story as true without question, she changed a number of details. Instead of a tomcat named Hamilton, she had Hamilton being called “Mrs. Washington’s Tom-cat.” She also had the story being printed in the Tory press, a detail not mentioned in the original. In her timeline, she had this taking place in 1777 instead of 1780. Granted, Gertrude Atherton’s The Conqueror was a work of historical fiction, but this book had much influence upon future generations of Hamilton biographers.

In 1946, Nathan Schachner wrote in his Hamilton biography:

His reputation as a gallant spread far beyond the confines of the camp.

A Tory newspaper managed to weave Hamilton’s notoriety and the proposed new American flag into a single withering sneer. “Mrs. Washington,” it reported, “has a mottled tom-cat (which she calls, in a complimentary way, ‘Hamilton’) with thirteen yellow rings around its tail, and that his flaunting it suggested to the Congress the adoption of the same number of stripes for the rebel flag.[3]

Despite quoting the original source, Schachner like Atherton placed this story in 1777 instead of 1780 and had it printed in a Tory newspaper. He also used this tale as proof of Hamilton’s “reputation as a gallant” and “notoriety,” something not mentioned in the original.

In 1999, Thomas Fleming wrote in Duel:

Martha Washington, in one of her droller moments, had nicknamed the house pet, a bigheaded, extremely amorous tomcat, “Hamilton”—a glimpse of his reputation as a ladies man in those days.[4]

Fleming, like his predecessors, reported this story as undoubtedly true. However, the mottled tomcat had by this time become a “bigheaded, extremely amorous tomcat,” information not found in the original. Moreover, the tomcat was named Hamilton, not “in a complimentary way” as originally reported, but because of his “reputation as a ladies man.”

In 2004, Ron Chernow wrote in his Hamilton bio:

Not for nothing did Martha Washington nickname her large lascivious tomcat “Hamilton.”[5]

With each new Hamilton biography, this tomcat apparently grows larger and more lustful.

Sealing the fate of this story in the public mind, the Hamilton musical contains the lines:

Burr: Martha Washington named her feral tomcat after him.

Hamilton: That’s true.[6]

Not only is the story repeated, with the tomcat being “feral,” but even Alexander Hamilton says the story is true. If Hamilton says it’s true, then it must be. Right?!?

A note by Lin-Manuel Miranda in Hamilton: The Revolution states:

This is most likely a tale spread by John Adams later in life. But I like Hamilton owning it. At this point in the story he is at peak cockiness.[7]

The story of Martha Washington’s tomcat has thus become so universally accepted that the original source has been all but forgotten. Somehow, it has become a story that was spread by John Adams, which no previous biographer mentioned.

In sum, this story has been repeated in dozens of Hamilton biographies as if it were undoubtedly true. They write that Martha Washington certainly had a tomcat and that this tomcat was “extremely amorous,” “lascivious,” and “feral.” They write that for this reason the tomcat was named Hamilton. On top of this, they write that it was reported in the Tory press during the American Revolution and some even note that the tale was “most likely” spread by John Adams “later in life.”

Returning to the Original Source

We started by quoting an anecdote written by Captain Smythe on January 1, 1780. Somehow, historians have strayed from this original source. A look at Captain Smythe’s entire entry will cast this story in a new light:

Thirteen is a number peculiarly belonging to the rebels. A party of naval prisoners lately returned from Jersey, say, that rations among the rebels are thirteen dried clams per day; that the titular Lord Stirling takes thirteen glasses of grog every morning, has thirteen enormous rum-bunches on his nose, and that (when duly impregnated) he always makes thirteen attempts before he can walk; that Mr. Washington has thirteen toes on his feet, (the extra ones having grown since the Declaration of Independence,) and the same number of teeth in each jaw; that the Sachem Schuyler has a top-knot of thirteen stiff hairs, which erect themselves on the crown of his head when he grows mad; that Old Putnam had thirteen pounds of his posteriors bit off in an encounter with a Connecticut bear, (’twas then he lost the balance of his mind;) that it takes thirteen Congress paper dollars to equal one penny sterling; that Polly Wayne was just thirteen hours in subduing Stony Point, and as many seconds in leaving it ; that a well-organized rebel household has thirteen children, all of whom expect to be generals and members of the High and Mighty Congress of the “thirteen United States” when they attain thirteen years; that Mrs. Washington has a mottled tom-cat, (which she calls, in a complimentary way, ‘Hamilton,’) with thirteen yellow rings around his tail, and that his flaunting it suggested to the Congress the adoption of the same number of stripes for the rebel flag.[8]

Let’s look at some of the anecdotes from Smythe’s entry.

“Thirteen is a number peculiarly belonging to the rebels… Lord Stirling takes thirteen glasses of grog every morning, has thirteen enormous rum-bunches on his nose, and that (when duly impregnated) he always makes thirteen attempts before he can walk ”

Is this true?

“Mr. Washington has thirteen toes on his feet, (the extra ones having grown since the Declaration of Independence,) and the same number of teeth in each jaw.”

Is this true?

“Sachem Schuyler has a top-knot of thirteen stiff hairs, which erect themselves on the crown of his head when he grows mad.”

Is this true?

“Old Putnam had thirteen pounds of his posteriors bit off in an encounter with a Connecticut bear, (’twas then he lost the balance of his mind).”

Is this true?

“Mrs. Washington has a mottled tom-cat, (which she calls, in a complimentary way, ‘Hamilton,’) with thirteen yellow rings around his tail, and that his flaunting it suggested to the Congress the adoption of the same number of stripes for the rebel flag.”

Is this true?

A Satirical Tomcat

Are any of the above anecdotes true? Did George Washington really have thirteen toes, the extras having grown since the Declaration of Independence? Did Lord Stirling really have thirteen rum-bunches on his nose? Did Philip Schuyler really have thirteen hairs on his head? Did Israel Putnam really have thirteen pounds of his posterior bit off by a bear? Did Martha Washington really have a cat with thirteen stripes on its tail? Did the idea of having thirteen stripes on the American flag really come from this cat?[9]

Obviously, this entire entry by Captain Smythe was a piece of sarcasm. It was all a joke. No one in 1780 would have believed any of these stories. No one now should believe them either.

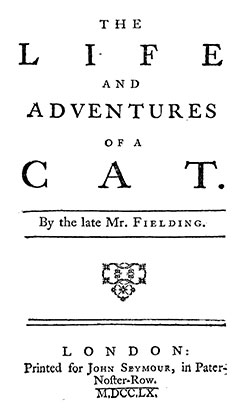

First Publication

Admitting 1) that the story was satire and 2) that Martha Washington had no tomcat, the fact that this Captain Smythe wrote about a tomcat being named Hamilton still shows that the British in 1780 knew that Hamilton was a “tomcat.” Right? Moreover, the tale was reportedly published in the “Tory press.” Thus, everyone knew that Hamilton was an “extremely amorous,” “lascivious,” “feral tomcat.” Right?

This story first appeared for public consumption in 1860 in Frank Moore’s Diary of the American Revolution.[10] In sharing the story, that book cites “Smythe’s Journal.”[11] The book’s “list of authorities” shows that this was the “Diary of Captain Smythe, of the Royal Army.”[12] In other words, this was a private journal or diary of a British officer. “Smythe’s Journal” was not a “Tory press” or newspaper. Thus, the tomcat story did not appear in the Tory press nor was it disseminated to the public in 1780.

Admitting 1) that the story was satire, 2) that Martha Washington had no tomcat, and 3) that the story did not appear in the press in 1780 and was not known until 1860, it is still a fact that this tale written in 1780 likens Hamilton to a “tomcat.” This still proves that Hamilton was widely known on both sides as an “extremely amorous,” “lascivious,” “feral tomcat.” Right?

Tomcat Defined

According to Google, a tomcat is defined formally as “a male domestic cat” but informally as “a sexually aggressive man; a womanizer.”[13]

Which of these two definitions did Captain Smythe have in mind? Was Smythe’s fictional “mottled tom-cat” just a male domestic cat? Or was Smythe’s fictional “mottled tom-cat” a “sexually aggressive” male cat?

To answer this, we are not interested in today’s definition of “tomcat.” We need to determine what the word meant in 1780.

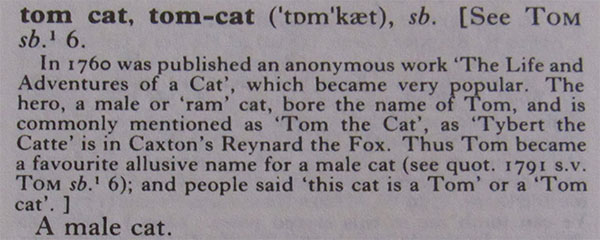

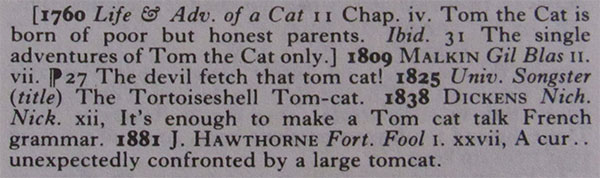

According to the Oxford English Dictionary:

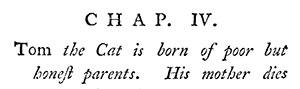

In 1760 was published an anonymous work ‘The Life and Adventures of a Cat’, which became very popular. The hero, a male or ‘ram’ cat, bore the name of Tom, and is commonly mentioned as ‘Tom the Cat’… Thus Tom became a favourite allusive name for a male cat…and people said ‘this cat is a Tom’ or a ‘Tom cat’.

The Oxford English Dictionary gives further examples of the word tomcat being used in literature. At least through 1881, tomcat simply meant a male cat and had no sexual connotation.

Likewise, Chambers’s English Dictionary of 1867, 1882, 1893, 1900, and 1904 defined tomcat as “A male cat, esp. when full grown.”[14] There was no mention of the male cat being lustful nor was there a second definition referring to a “sexually aggressive man; a womanizer.”

Similarly, Webster’s Dictionary defined tomcat in 1879, 1905, and 1917 simply as “a male cat.”[15] Again, there was no reference to the cat being lustful or a second definition of a “sexually aggressive man; a womanizer.”

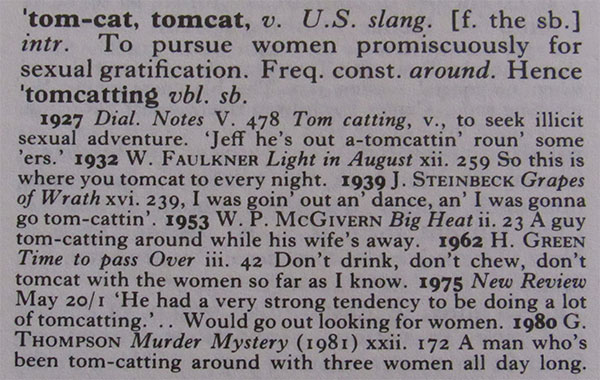

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest reference they could find for tomcat with a sexual connotation was in 1927 for the verb form, meaning “to pursue women promiscuously for sexual gratification.”

Today’s Merriam Webster’s Dictionary also gives a date of 1927 for tomcat meaning “to seek sexual gratification promiscuously.”[16]

Thus, when Captain Smythe made up a story about a tomcat in 1780, the word tomcat meant “a male cat” and nothing more. The term tomcat had no sexual connotation at that time. Accordingly, Captain Smythe never meant for Hamilton to be seen as an “extremely amorous,” lascivious,” “feral tomcat.” In fact, Smythe wrote that Martha name the tomcat Hamilton “in a complimentary way.” The tomcat story was never meant to disparage Hamilton.

The Tomcat Fully Refuted

In conclusion:

- Martha Washington did not have a tomcat named Hamilton and probably didn’t even have a tomcat at all. Certainly, she did not call Alexander Hamilton a tomcat.

- The tomcat story was a satirical tale written in 1780 by Captain Smythe in his private journal.

- Captain Smythe did not call Hamilton a “tomcat” nor did he imply that a tomcat was named after him because of his reputation.

- The tomcat story first appeared in print in 1860.

- The word “tomcat” had no sexual connotation when the story was written in 1780 or when it was first published in 1860.

As with last week’s blog post, yet another story supposedly proving that Hamilton actively pursued the ladies and was a “tomcat” has been proven false.

The final conclusion: ALEXANDER HAMILTON WAS NO TOMCAT!

Notes

This essay is based on a lecture given July 7, 2016, at Liberty Hall Museum as part of CelebrateHAMILTON 2016.

Here is the slideshow that was used during that lecture:

The lecture was widely covered by the media. The Associated Press wrote about it under the title “A Hamilton tale too tall? Group disputes tomcat story.” The AP story was then republished by NBC New York, The Washington Times, The Boston Globe, the San Francisco Chronicle, The Seattle Times, Entertainment Weekly, the New Delhi Times, and many others. Local coverage included TV media and the story was independently reported by NJ.com and the Union News Daily.

Announcements

There will be no blog post next week because of the Jewish holiday of Shavuot. The next blog post is scheduled for May 29, delayed one day because of Memorial Day.

Please join me tomorrow (May 15) at 6 p.m. at the Anderson House in Washington, DC, for the Society of the Cincinnati 235th Anniversary lecture. I will be speaking about Alexander Hamilton’s Revolutionary War Service.

Endnotes

[1] “Smythe’s Journal,” January 1, 1780, excerpted in Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution 2:250.

[2] Gertrude Atherton, The Conqueror 163.

[3] Nathan Schachner, Alexander Hamilton 92.

[5] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton 126.

[6] Lin-Manuel Miranda, “A Winter’s Ball,” Hamilton.

[7] Lin-Manuel Miranda, Hamilton: The Revolution 70.

[8] “Smythe’s Journal,” January 1, 1780, excerpted in Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution 2:250.

[9] The Grand Union Flag with thirteen stripes made its first appearance in December 1775, long before Hamilton and Martha Washington first met.

[10] Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution vol. 2 and 2:250.

[11] “Smythe’s Journal,” January 1, 1780, excerpted in Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution 2:250.

[12] Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution 1:vi.

[13] Google search: Define tomcat.

[14] Chambers’s English Dictionary of 1867, 1882, 1893, 1900, and 1904.

[15] Webster’s Handy Dictionary of 1879 and 1905; Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary of 1917.

[16] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th Edition (2004), 1315.

© Posted on May 14, 2018, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.