Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

© Posted on January 8, 2018, by Michael E. Newton.

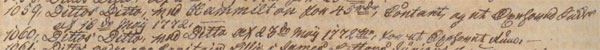

In a 1939 essay,[1] H. U. Ramsing shared his discovery of numerous entries in the probate record of a Thomas Lillie of St. Croix relating to the estate of James Lytton, Alexander Hamilton’s uncle. Among the hundreds of entries are dozens pertaining to Ann Lytton Venton, the daughter of James Lytton and Alexander Hamilton’s first cousin. Among these entries for Ann Lytton Venton are four quittances [receipts] “with” Alexander Hamilton for 120 rigsdalers, 1 hogshead of sugar, and 1 hogshead of rum. There is also one “order in favor of Alexander Hamilton” for 15 hogsheads of sugar. These entries are dated May 16 and 23, 1772, May 3 and 26, 1773, and June 3, 1773.[2]

While H. U. Ramsing found these entries in Thomas Lillie’s probate record, which was compiled in 1780, they actually appeared in another volume back in 1776.

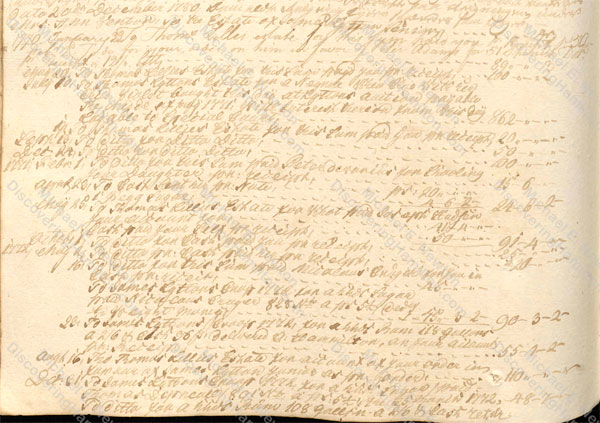

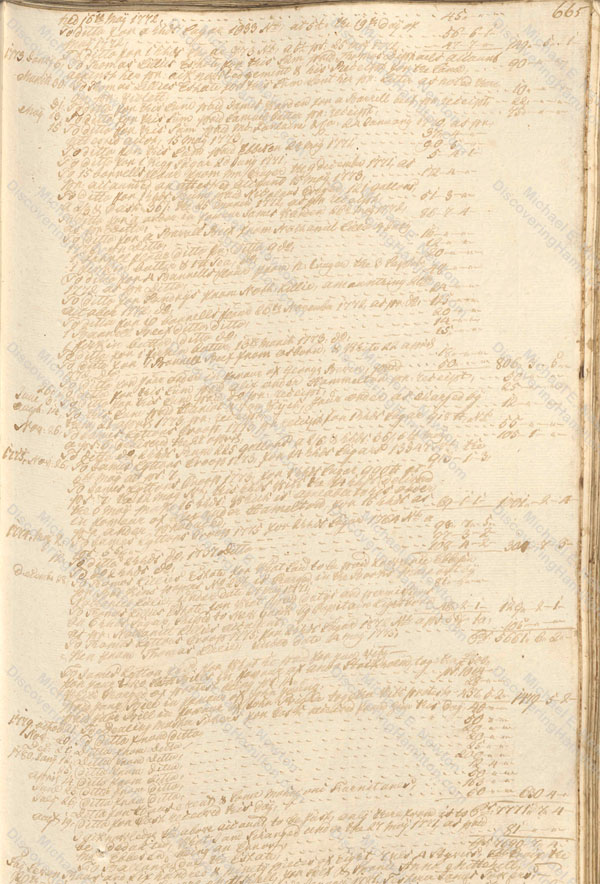

As can be seen from the above images and the corresponding entries in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton,[3] the records of these four quittances and one order are mere summaries and are missing information vital to understanding the transactions.

New Records Discovered

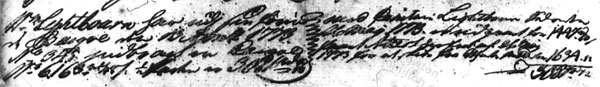

Fortunately, these transactions appear in more detail in another location. Overlooked by H. U. Ramsing and others, the probate record of James Lytton contains a list of dozens of debits for “Mrs. Ann Venton, To the Estate of James Lytton Senior.”

On May 16, 1772, Ann Lytton Venton debited 45 rigsdalers from her father’s estate and also debited one hogshead containing 828 pounds of sugar, valued at 45 rigsdalers, 3 reals, and 2 styvers. Both the money and the sugar were “paid [to] Nicolaus Cruger.”

These two transactions match exactly Ann Lytton Venton’s quittance with Hamilton of the same date.[4] Clearly, Nicholas Cruger had acted as Hamilton’s banker in this transaction.

A week later, on May 23, 1772, Ann Lytton Venton debited her father’s estate one hogshead containing 118 gallons of rum “delivered [to] A. Hammilton, on your account per receipt,” with a value of 55rdl 1r 2st.

This transaction also matches Ann Lytton Venton’s quittance with Hamilton of the same date.[5]

The following year, on May 26, 1773, Ann Lytton Venton debited her father’s estate 50 rigsdalers for the “sum paid Alexander Hammelton pr. receipt.” A week later, on June 3, Ann Lytton Venton paid Hamilton another 25 rigsdalers.

These transactions again match two of Ann Lytton Venton’s quittances as found in Thomas Lillie’s probate record.[6]

Two more transactions appear on November 26, 1773. The first transaction, which is backdated to May 6, 1773, is for “14 hogsheads sugar,” holding 13,347 pounds of sugar, and valued at 913rdl 1r 3st. This is followed by another transaction, backdated to May 12, 1773, for “1 hogshead sugar” with 990 more pounds of sugar valued at 69rdl 1r 1st, with an additional note that “this hogshead with the 14 hogsheads delivered the 6th May make the 15 hogsheads which is agreeable to his order in favor of Alexander Hamelton for 15 hogsheads.” The value of these 15 hogsheads of sugar totaled 1001rdl 2r 4st.[7]

These 15 hogsheads of sugar are clearly the same as those mentioned in Ann Lytton Venton’s order in favor of Alexander Hamilton dated May 3, 1773.[8]

Alexander Hamilton’s generous cousin also appears to have paid some or all of the costs of sending the May 1773 sugar to him in New York. An undated record states that Ann Lytton Venton paid “dutys and permissions” of 48 rigsdalers “on 6 hhds sugar shipped to New York by Captain Lightbourn.”

Other records show that Captain William Lightbourn was outbound from Christiansted sailing for New York on May 25–26, 1773, suggesting that the above six hogsheads of sugar may have been part of the fifteen hogsheads sent to Hamilton at this time.

If Ann Lytton Venton did indeed pay the shipping costs on these six hogsheads of sugar, it is likely she paid the costs of the other nine as well and possibly paid for other expenses Hamilton may have incurred during his move from St. Croix to the North American mainland. If so, these additional payments by Ann Lytton Venton were not recorded or the records of those transactions have not yet been found or no longer exist.

Ann Lytton Venton Pays for Alexander Hamilton’s Education

Many have argued that Alexander Hamilton, in receiving the above money, sugar, and rum, had acted as Ann Lytton Venton’s “middleman,” presumably to prevent her husband, from whom she had separated, from collecting her share of the proceeds from the estate of her father James Lytton.[9] The records, however, as displayed above, clearly show that Ann Lytton Venton regularly debited her father’s estate without the need of a “middleman.” Thus, it is clear that the above transactions involving Alexander Hamilton were gifts to him.

As Hamilton by the time of these transactions had a good job working as head clerk for Nicholas Cruger and had lived for many years without apparent financial support from his cousin, he presumably did not need these funds from Ann Lytton Venton for his everyday living. Based on later events, it is clear that these gifts were to help Alexander Hamilton pay for his education on the mainland. Accordingly, the funds given to Hamilton by his cousin in May 1772 are the first indications that Hamilton was planning and even preparing to go to the mainland for school, further dispelling the notion that Hamilton had only been sent to North America for an education as a direct result of the impression left by his account of the great hurricane,[10] which was not written until five months later and not published until after he had already left the island.[11]

Based on the figures provided in these newly discovered records, it is clear that Ann Lytton Venton was Alexander Hamilton’s primary if not sole benefactor. Her gifts of May 1772 consisted of forty-five rigsdalers, a hogshead of sugar, and a hogshead of rum, valued at precisely 145rdl 4r 4st according to the records of the Lytton estate, or approximately £23 sterling. Ann Lytton Venton’s gifts of May and June of 1773 provided Hamilton with another fifteen hogsheads of sugar and seventy-five rigsdalers, worth precisely 1,076rdl 2r 4st, or about £172 sterling. This brought the total value of Ann Lytton Venton’s gifts to Alexander Hamilton to exactly 1,221rdl 7r 2st, or about £196 sterling, at a time when the average British worker earned just £16 per year.[12]

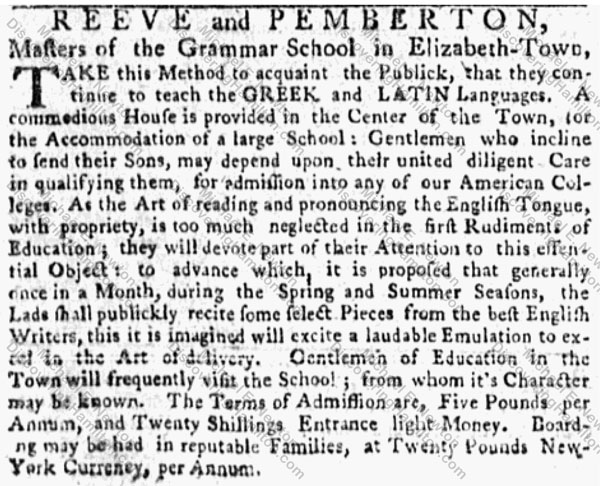

Ann Lytton Venton’s gifts to Alexander Hamilton were expected to cover all or most of Hamilton’s educational expenses. According to a 1767 advertisement, the grammar school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, which Hamilton would attend, charged twenty shillings for admission, five pounds per year for tuition, and twenty pounds per year for boarding with a local “reputable” family.

The cost of a year at this grammar school totaled twenty-six pounds New York money, or about £15 sterling. Hamilton, of course, would have additional expenses, such as travel and clothing. Thus, Ann Lytton Venton’s gifts of May 1772 of about £23 sterling was more than enough to get Alexander Hamilton started and was perhaps enough to cover the first year at the grammar school he attended.

As for college, tuition at King’s College was six pounds New York currency per annum, rent was four pounds per year, and meals cost eleven shillings per week, or about twenty-five pounds per year.[13] Other expenses would have included tutoring, clothing, books, paper, pencils, firewood, candles, and travel.[14] In total, King’s College cost an estimated £50 to £80 New York currency per year, £200 to £320 for a full four years, or about £112 to £180 sterling.[15] Tuition at the College of New Jersey was one-third less than at King’s College while food and rent were also considerably cheaper.[16] Hamilton hoped to further reduce the cost of his college education by demanding that he be “permitted to advance from class to class with as much rapidity as his exertions would enable him to do.” Although the College of New Jersey rejected these terms, King’s College accepted Hamilton on the same “terms he had proposed at Princeton.”[17]

Thus, the £172 sterling Ann Lytton Venton had given Hamilton in 1773 probably was sufficient to cover any remaining expenses from his year in grammar school plus the cost of four years in college, and she surely offered to provide him with additional funds if these were insufficient. Although others may have contributed to Hamilton’s education fund, it is clear from these records that Ann Lytton Venton was Alexander Hamilton’s primary if not sole benefactor.

In the end, Alexander Hamilton spent just two and a half years at King’s College before “the American Revolution supervened.”[18] He used what remained in his education fund, provided to him entirely or mostly by Ann Lytton Venton, to equip the artillery company he raised in early 1776.[19]

Ever thankful for his cousin’s generosity, Alexander Hamilton wrote in his final letter to his wife that Ann Lytton Venton (by this time known as Ann Mitchell) was “the person in the world to whom as a friend I am under the greatest obligations.”[20] As the person who paid for Alexander Hamilton’s education on mainland North America, thereby launching his American career, the little-known Ann Lytton Venton Mitchell deserves our gratitude, just as she had earned the gratitude of her cousin Alexander Hamilton.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

[1] H. U. Ramsing, “Alexander Hamilton og hans Mødrene Slaegt.”

[7] The numbers given in the records don’t add up. Adding 913rdl 1r 3st and 69rdl 1r 1st totals 982rdl 2r 4st, not 1,001rdl 2r 4st. The 69rdl 1r 1st is probably correct because 990 pounds of sugar at the listed 7 rigsdalers per hundredweight totals 69rdl 2r 2st, nearly the same as the amount recorded. However, 13,347 pounds of sugar at 7 rigsdalers per hundredweight would total 934rdl 2r 2st, well above the 913rdl 1r 3st recorded. The 14,337 pounds of sugar at 7 rigsdalers per hundredweight should total 1,003rdl 4r 4st, close to the 1,001rdl 2r 4st given.

[9] H. U. Ramsing, “Alexander Hamilton og hans Mødrene Slaegt”; Chernow, Alexander Hamilton 39.

[10] In Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, I asserted that “the hurricane and Hamilton’s account of it may have had nothing to do with his move to the mainland” and that “all that rhetoric about Hamilton riding a whirlwind into history appears to be mistaken.”

[11] Newton, Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years 57–58 and 59–60.

[12] “The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain.”

[13] A History of Columbia University 27 and 40.

[14] Humphrey, From King’s College to Columbia 252.

[15] Humphrey, From King’s College to Columbia 93–94.

[16] Humphrey, From King’s College to Columbia 91–92.

[17] Hercules Mulligan, “Narrative.”

[18] Alexander Hamilton to William Hamilton, May 2, 1797, in PAH 21:77.

[19] John C. Hamilton, The Life of Alexander Hamilton 1:52; John C. Hamilton, History of the Republic 1:121.

[20] Alexander Hamilton to Elizabeth Hamilton, July 10, 1804, in PAH 26:307.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

Excellent information! Thank you for this post.

You are welcome. Glad you enjoyed it.

Fantastic revelation. I’m wondering if she had political connections on the mainland, or through Rev. Knox, which would have facilitated Hamilton’s integration into revolutionary networks in New York and New Jersey.

Ann Lytton Venton had lived on the mainland for a few years before returning to St. Croix. There is no indication that she had any influential connections. But Hamilton had plenty of connections through Nicholas Cruger, David Beekman, and Cornelius Kortright, scions of three of NY’s most influential families. Hugh Knox, of course, had connections too to the academic world, especially the College of New Jersey and therefore also the grammar school in Elizabethtown.

In time, I’ll be presenting some new discoveries in this arena. Patience…

Women always seemed to be of importance to our hero

Behind every good man is a good woman. Hamilton had at least three good women behind him: his mother, his cousin, and his wife.

This is some amazing information! I just read Hamilton’s final letters to Eliza and noticed the mention of “Mrs. Mitchell”, who the footnotes identified as his cousin, and went looking for more information and found this page. Do we know of anything more about her? He told Eliza that he had “encouraged her to come to this Country and intend, if it shall be in my power to render the Evening of her days comfortable.” Looking at the information you provided, it makes sense why he sounds so beholden to her, wanting to support her in her golden years. She’s the one who made it possible for Hamilton to do all that he did. Hamilton raised himself up, but Ann was the one who gave him the means to establish the foundation for him to do so. From what I’ve found just from the letters on Founders Online, Ann died in 1827 at Christiansted. Is there any other evidence of her presence in Hamilton’s life, or the lives of his family after his death?

Thanks again for sharing this!