One of the great things about discovering something new about historical figures is that it prompts others to look for more information in places no one ever thought of looking. After my discovery that the Hamiltons had spent more time on St. Eustatius than previously known (see Discovering Hamilton or this lecture), a number of researchers, in addition to myself, started searching for records of James Hamilton, Rachel Faucett Lavien Hamilton, and their two sons on that Dutch island. It did not take long for this to yield results.

Finding James Hamilton in the St. Eustatius Censuses

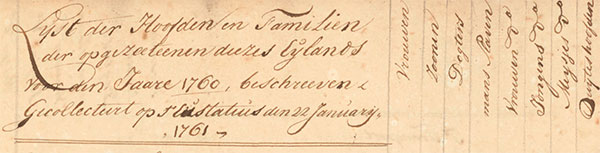

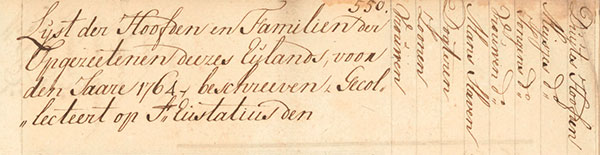

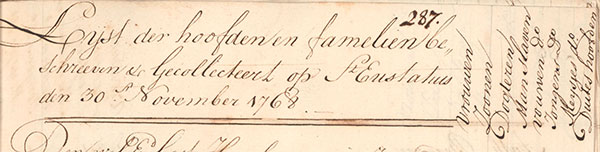

The first place to look for anyone on St. Eustatius would, of course, be in that island’s census records. Unfortunately, when I presented my new discoveries, the censuses were not available online. I believed that seeing these records would have required a trip to the Netherlands or finding someone with access to the archival records there. While this made it impossible for me, at the time, to get the census records, some researchers more familiar with the records concerning St. Eustatius had read my work and conducted their own searches.

Here is a brief history, as far as I understand it, of how James Hamilton and family were found in the St. Eustatius records:

Shortly after my St. Eustatius revelations, which were presented and published in July 2019, I heard in either September or October 2019 from Walter Hellebrand, the director of the St Eustatius Monuments organization, that he had found records of James Hamilton and family in the St. Eustatius census. He did not share the details with me, but I then did a web search and found that Eliza Gramarye, at the time a graduate student at the University of Rochester, had transcribed a number, but not all, of the St. Eustatius censuses. Two of these (1764 and 1766) listed a James Hamilton and the details regarding the size of his family made it clear that this was Alexander Hamilton’s family (I’ll get into the details of the census records later). This confirmed that Walter Hellebrand had indeed found James Hamilton, Rachel Faucett Lavien Hamilton, and their two sons, James Jr. and Alexander, in the St. Eustatius census. As these were not my discoveries, despite finding them in publicly available online sources, I chose not to share them and left it to Mr. Hellebrand to do so.

I then heard in August 2020 from Ruud Stelton, an archaeologist working and living on St. Eustatius, that he had found evidence putting the Hamiltons on St. Eustatius. Mr. Stelton did not tell me anything about this evidence, but knowing about the census records, I guessed that this is what he had found. In October 2020, Ruud Stelton and Alexandre Hinton published their findings at the Journal of the American Revolution.

Seeing that the discovery had been made public, Walter Hellebrand in February 2021 shared that he had made the same discovery.

This is the timeline as far as I understand it and was witness to parts of it. I hope and believe that I got it correct.

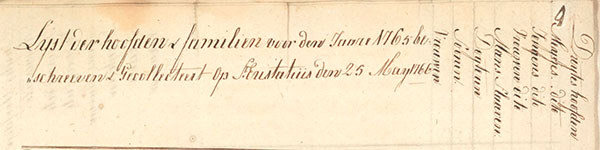

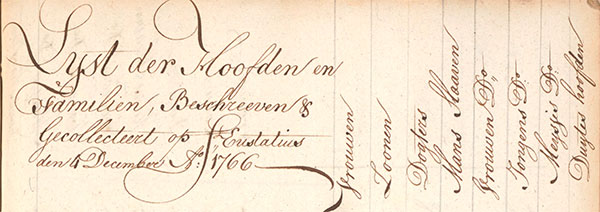

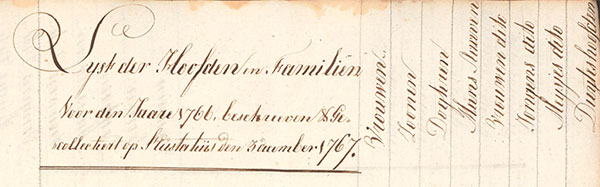

Subsequent to all this, the Nationaal Archief, the national archives of the Netherlands located in The Hague, made available online digital images of many of their collections, including some that included the St. Eustatius census records. In addition to having the details provided by Ruud Stelton and Alexandre Hinton in their essay, I was now able to see the original records (links to the original records and images of the relevant sections are provided below). Also, Eliza Gramarye “collated” the census data from 1746, 1758, and 1766, making it easier to see trends in the data. She also wrote “a demographic analysis of 18th century St. Eustatius,” providing additional context. While I will focus on James Hamilton and his family in this essay, I have found Gramarye’s essay, along with the essay by Stelton and Hinton, useful in understanding life on St. Eustatius at this time, which hopefully will find its way into a future about Alexander Hamilton’s early life.

Previous Information about James Hamilton and Family, 1753–1765

Before delving into the St. Eustatius censuses, it pays to recall what was previously known about the Hamiltons on St. Eustatius, as shared in Discovering Hamilton and this lecture. In 1753, James Hamilton “absented himself” from St. Kitts to St. Eustatius “on account of debt.” Rachel followed him. After moving back to St. Kitts and/or Nevis, Rachel and James returned to St. Eustatius by the end of 1756. They are found there still, or again, in 1757 and in October 1758. After 1758, James, Rachel, and their children disappear again from the known records until James arrived on St. Croix in April 1765 and the rest of the family apparently followed shortly afterwards.

Now to the St. Eustatius censuses. . . .

1753

James Hamilton was not listed in the 1753 census even though he “absented himself” from St. Kitts to St. Eustatius sometime in 1753.

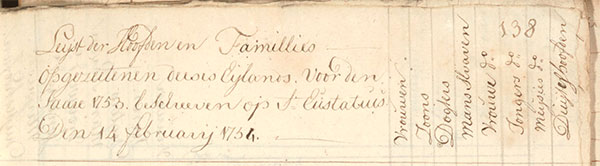

1754

James Hamilton does not appear in the 1754 census. Evidence suggests that the Hamiltons had moved back to St. Kitts and/or Nevis in 1754.

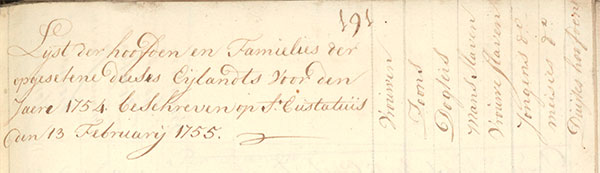

1755

Nor does he appear in the census of 1755.

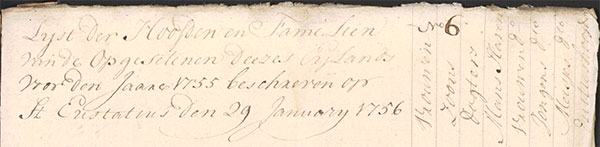

1757

The next census that has been found was that of 1757 (either no census was conducted in 1756 or the record has not been found). Still no James Hamilton, even though he had returned to St. Eustatius by the end of 1756 and was found there in both 1757 and 1758.

1758

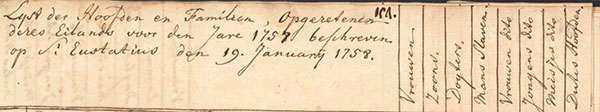

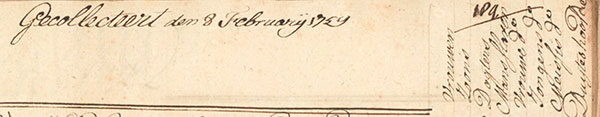

The next census, which must have covered 1758 (no year is given), was conducted on February 8, 1759. Yet again, no James Hamilton in listed.

1759

In the census of 1759, James Hamilton appears for the first time, but no one is counted with him and he did not pay the head tax. Accordingly, it would seem that James Hamilton’s family was living elsewhere at this time. Perhaps James was also absent since he did not pay the head tax. There are records of the Hamilton on St. Eustatius in 1756, 1757, and 1758 (Discovering Hamilton and this lecture), so it’s not quite clear how or why they escaped being counted. Perhaps non-residents could stay on the island temporarily and avoid being counted and paying the head tax by claiming to be there temporarily. If James was a sailor, as records show he later was, or was a merchant who did business on multiple islands, he could claim to be a foreigner and perhaps not be counted.

1760

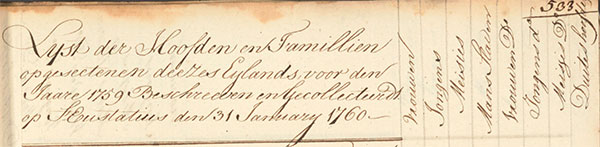

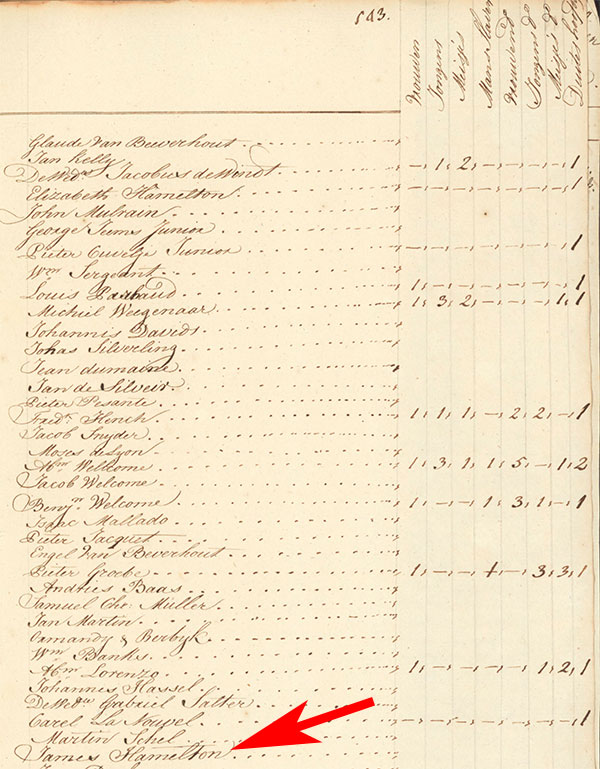

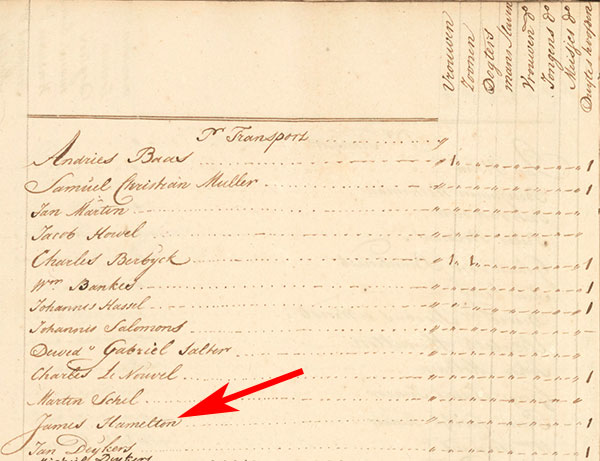

The next census of 1760, two copies of which have been found (copy1 and copy2), again shows James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) without his family and with no slaves. This time, however, he paid the head tax for himself. This suggests that James Hamilton may have been spending more time on St. Eustatius.

1761

In the census of 1761, two copies of which have also been found (copy1 and copy2), James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) appears by himself. Interestingly, he did not pay the head tax even though he had the previous year.

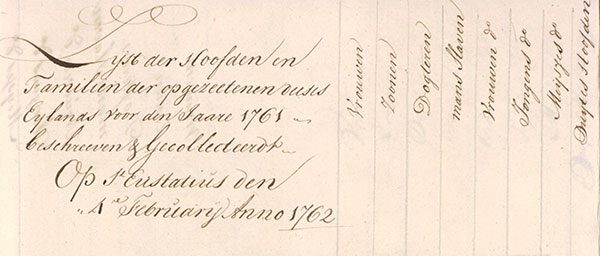

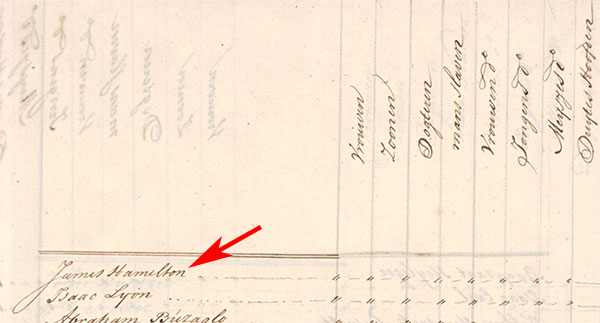

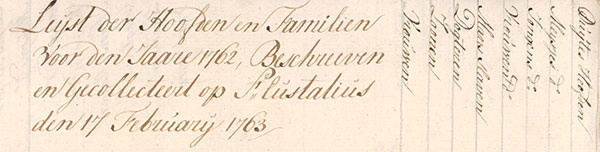

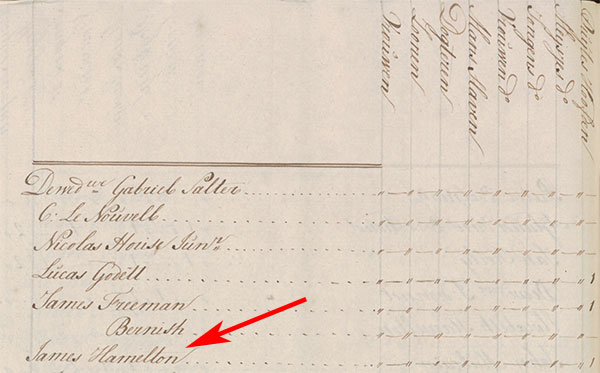

1762

The census of 1762, two copies of which have also been found (copy1 and copy2), shows James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) by himself. He paid the head tax for one person after not paying it the previous year.

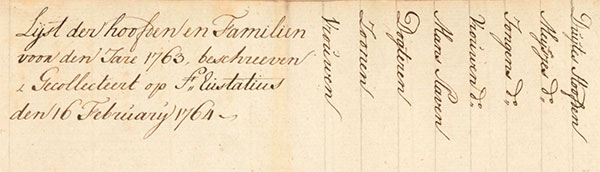

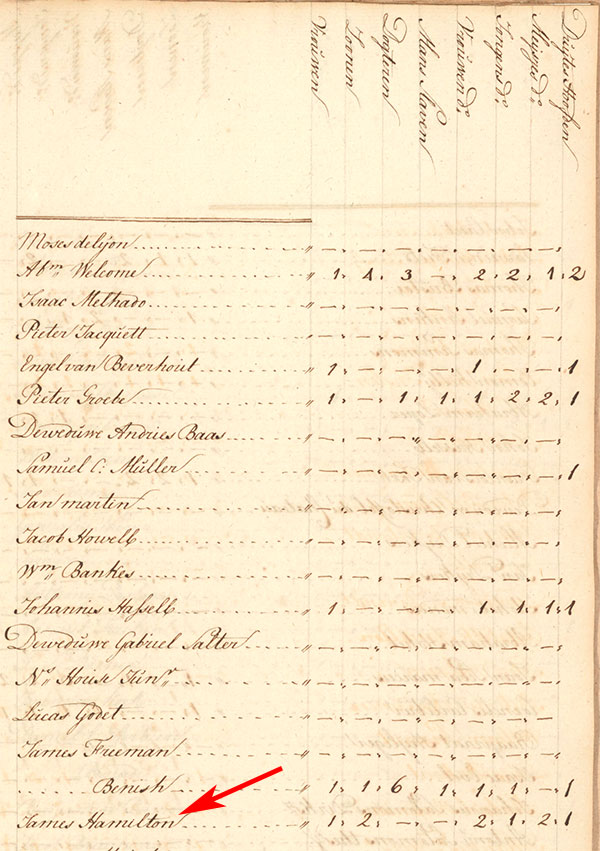

1763

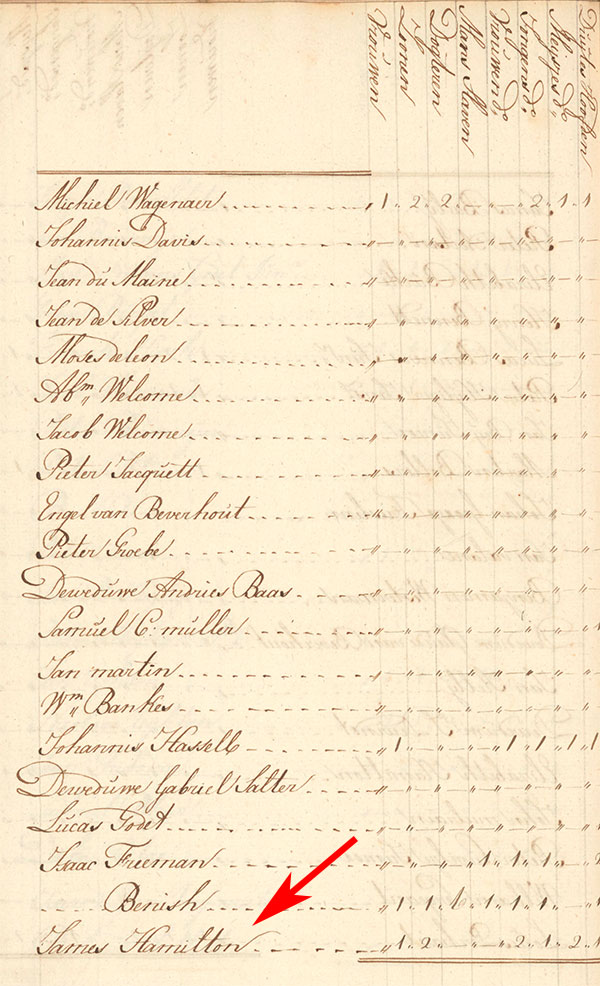

The census of 1763 (copy1 and copy2), again lists James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2), this time with 1 wife, 2 sons, 2 enslaved women, 1 enslaved boy, and 2 enslaved girls. Clearly, the 1 wife was Rachel Faucett Lavien Hamilton and the 2 sons were James Jr. and Alexander. James Hamilton paid the head tax on one person (himself).

Clearly, the family were now considered permanent residents and had their slaves with them on the island. Does this mean that Rachel and the children only came to St. Eustatius in 1763? This would seem unlikely since James had been on the island according to the census in some form or another since at least 1759 and other evidence shows them on the island in 1756, 1757, and 1758.

It is also interesting that the slaves appear at the same time as Rachel and the children. Perhaps these slaves belonged to Rachel rather than James since James had none listed with him prior to Rachel’s arrival and it is known that Rachel inherited slaves from her mother in 1756 or soon thereafter (Deed of Trust, May 5, 1756, in the Common Records of St. Kitts, quoted in Atherton, “The Hunt for Hamilton’s Mother” 237–238).

Owning five slaves appears to put the Hamiltons in the white middle-class of the island. As Stelton and Hinton point out, “To place the Hamiltons’ number of enslaved into perspective, one has to look at the entire Statian population at this time. The island’s census records from 1764 reveal 182 out of 588 heads of households to be enslavers. Some people had large numbers of enslaved, such as merchant and future Governor Johannes de Graaff, who enslaved fifty-one, but most only enslaved a few. The average number of persons enslaved by individuals on the island in 1764 was 7.2. From this data, it can be concluded that the Hamiltons were among the 31 percent of families on the island who actually enslaved persons, but enslaving slightly below the average number. This data provides some insight into the Hamiltons’ standing within society and suggests they were comfortably situated within the island’s middle class.”

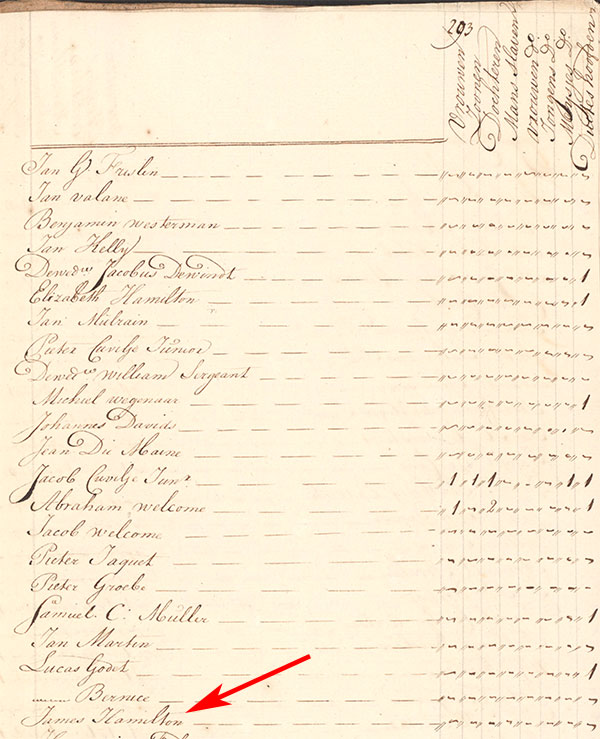

1764

The next census, that of 1764 (copy1 and copy2), shows James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) with 1 wife, 2 sons, 2 enslaved women, 1 enslaved boy, and 2 enslaved girls, the exact same numbers as the year before. He paid the head tax on one person (himself).

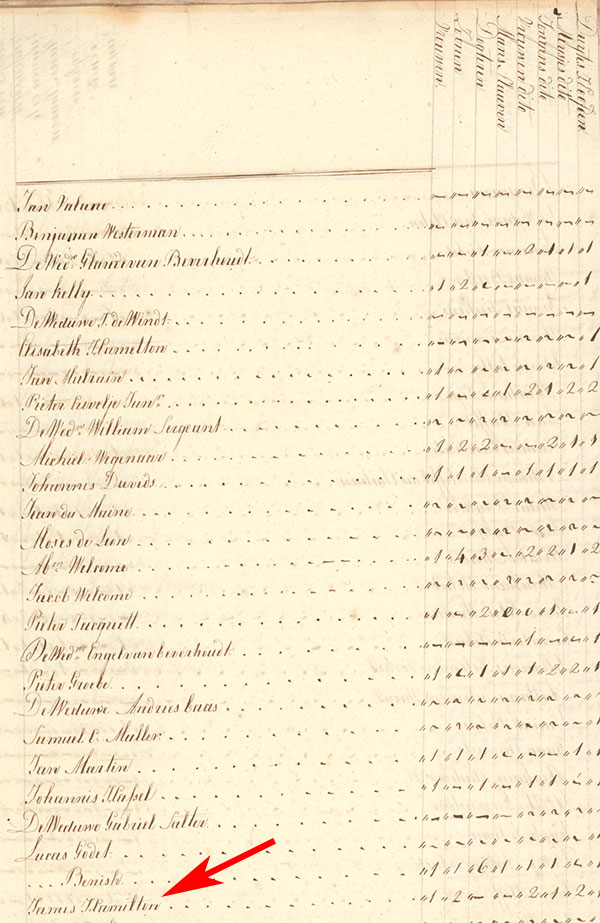

1765

The next census covered the year 1765. As in the previous two censuses, it shows James Hamilton with 1 wife, 2 sons, 2 enslaved women, 1 enslaved boy, and 2 enslaved girls. He paid the head tax. What’s interesting here is that the James Hamilton had left St. Eustatius by February 1765 and arrived on St. Croix in April 1765, with his wife and children following shortly thereafter. “Rachael Fatzieth” with her two sons and one slave appear in the St. Croix census on January 14, 1766. James Hamilton himself appears in St. Croix court records throughout 1765 and early 1765 and appears as a witness on St. Croix on June 25, 1766.

How could the Hamiltons be listed in the St. Eustatius census when they clearly were living on St. Croix in 1765? Probably they were counted in this census because they had lived on St. Eustatius for part of the 1765 calendar year. Of course they were also on St. Croix in 1765, so they were counted there as well. Interestingly, it was only Rachel and her children who were counted on St. Croix whereas they along with James were all counted on St. Eustatius. Despite arriving on St. Croix in his employ as a sailor and staying as an attorney for Archibald Ingram of St. Kitts, James must have maintained his residency on St. Eustatius rather than officially move to St. Croix, whereas Rachel and the children became residents of St. Croix. Perhaps Rachel’s previous marriage on St. Croix and restrictive divorce granted to her former husband on this island prevented her and James from being listed together. And since it was Rachel who owned the slaves, it was she who was listed in St. Croix census. James Hamilton may have lived with her and the children when he was on the island, but for legal reasons he could not be seen as being the head of the household or even living with her, so he maintained his foreign status while on St. Croix and kept his residency on St. Eustatius. Of course, this is just speculation. The extant record simply does not provide enough detail for a complete understanding of the situation.

1766

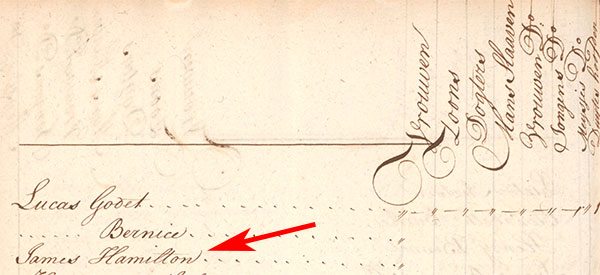

The next census, which bears a date of December 4, 1766, and presumably covers the year 1766, of which there are two copies (copy1 and copy2), shows James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) by himself and not paying any head tax. Clearly, his family was no longer on the island and it is possible that he was not either. As Rachel and the children appear in the St. Croix censuses at this time and James Hamilton was on St. Croix first as a sailor and then collecting a debt for Archibald Ingram throughout 1765 and into early 1766 and is again found on St. Croix in June 1766, it would appear that he was no longer a resident of St. Eustatius. However, he is not found in the St. Croix census either. Perhaps he escaped having to pay the head tax as he continued his work as a sailor and never spent enough time on the island to be considered a permanent resident. Or possibly he had abandoned St. Eustatius and St. Croix and made St. Kitts his home yet again.

1767

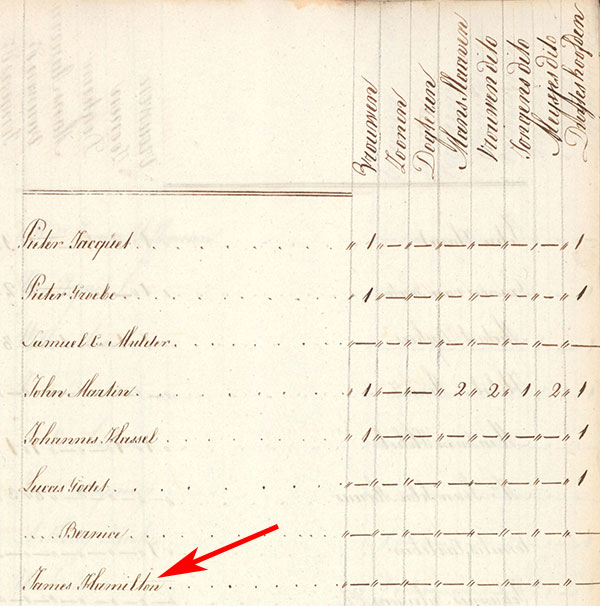

Like the previous year, the 1767 census (copy1 and copy2) shows James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) by himself and not paying any head tax. By this time, James Hamilton’s whereabouts are not known. He is listed in the St. Eustatius census, but he is not paying the head tax, so it is not clear whether he lived on St. Eustatius, was a frequent visitor, or just remained on the census rolls without ever coming to the island.

1768

As in the previous two years, the 1768 census (copy1 and copy2) shows James Hamilton (copy1 and copy2) by himself and not paying any head tax.

1769

James Hamilton no longer appears in St. Eustatius’s censuses starting in 1769 (copy1 and copy2). If he had not already left the island years earlier, he certainly had done so by this time. He is next found on Bequia in 1774.

What do the St. Eustatius Censuses Reveal about the Hamiltons? What is Missing?

James Hamilton does not appear in the St. Eustatius census until 1759, but previously discovered records clearly show that James Hamilton along with Rachel and their children spent considerable time on St. Eustatius in 1753, 1756, 1757, and 1758. Perhaps the Hamiltons considered their residence on St. Eustatius at this time as being of a temporary nature. If James Hamilton worked at this time as a sailor, as he would later, or perhaps as a merchant doing business on multiple islands, he may have spent but little time on St. Eustatius and thereby evaded both the tax collector and census taker.

James Hamilton appears in the St. Eustatius census without wife, children, or slaves during the years 1759 through 1762. It is not clear why James Hamilton would appear now but not in the previous years or why he appeared by himself without his family. Possibly James Hamilton had been spending increasing amounts of time on St. Eustatius that he finally made that his home or the authorities forced him to do so. But where were his wife and children? Perhaps they spent most of their time on St. Kitts or Nevis rather than on St. Eustatius. Or perhaps they were living on St. Eustatius, as they were in 1756, 1757, and 1758, but escaped being counted for any number of reasons. In fact, a look at the census records shows few or no female heads of household besides some widows. Since Rachel was not married to James Hamilton, legally speaking, nor was she a widow, it is possible she escaped the census taker.

In the years 1759, 1761, and 1766–1768, James Hamilton paid no head tax, but in 1760 and 1762–1765 he did. Regarding the head tax, Stelton and Hinton conjecture, “The 1764 census records show that in this year, 358 out of 588 heads of households were exempted from head tax, so this was quite common. This suggests that there were probably several conditions or prerequisites that resulted in an exemption. A few possible explanations for the exemption could be that if James was still traveling between islands, doing various jobs such as sailing and debt collecting, or did not own any taxable property, head tax might not have been extracted from him on St. Eustatius.” As a result, as with so much else, there are a number of possible reasons why James Hamilton paid or did not pay the head tax in any individual year. It is difficult to draw a conclusion about whether James lived on St. Eustatius or how much time he spent on the island based solely on whether he paid the head tax.

In the years 1763–1765, Rachel and the two children and counted with James Hamilton. Does that mean they arrived on St. Eustatius in 1763 but were not on the island previous to this? But we know that they were on the island in 1753, 1756, 1757, and 1758. Again, there are many possible reasons why they would not have been counted on St. Eustatius even though they were on the island. Possibly they split their time between St. Eustatius, St. Kitts, Nevis, and/or other islands. Another possible reason is that Rachel’s previous marriage prevented her from being counted as James Hamilton’s wife. And since the census does not appear to list women heads of household besides widows, she may have escaped notice. Alternatively, perhaps after a certain amount of time, the Dutch authorities finally accepted Rachel as James Hamilton’s wife and at that point counted her and their children with James. Previous to that, they may have been on the island but not counted for one or more of the various reasons proposed above by myself or by Stelton and Hinton.

It is also interesting that Rachel and the children were counted with James Hamilton in the 1765 census when the whole family had moved to St. Croix in the spring of 1765. It would appear that since they had lived part of 1765 on St. Eustatius and part on St. Croix, Rachel and the children were counted in both places. James Hamilton, however, who was on St. Croix in most of 1765 and 1766, was never counted on St. Croix but was counted both years on St. Eustatius. His time spent on St. Croix was first as a sailor and then as an non-resident attorney for Archibald Ingram, so he perhaps escaped the double counting and the double taxation that way.

Now, in 1766, James Hamilton is again listed on St. Eustatius without his wife and children, but he does not pay the head tax. Was James Hamilton left in the census records because he had been there in previous years but the numbers left blank because he and his family were no longer there? Or was James living on St. Eustatius but exempt for some reason from paying the head tax? Or was he a part-time resident, listed but not counted? While the records show that Rachel and the children lived on St. Croix, James’s whereabouts after June 1766 are not known. He may have returned to St. Eustatius or at least spent part of his time there, or perhaps he did not return to St. Eustatius but his name was simply carried over from previous censuses without his being on the island.

In summary, James Hamilton, Rachel, and the two children were clearly residents of St. Eustatius from 1763 to 1765 and Rachel during this time was considered by the census takers to be James’s wife (but they may have relied on statements by James and Rachel and presumably did not check to see whether they were legally marriage). Evidence showing the Hamiltons on the island in 1756, 1757, and 1758 suggests they may have lived there the entire time from 1756 to 1765. If Rachel and the children lived on St. Eustatius prior to 1763, they were not counted with James, perhaps because of her previous marriage and restrictive divorce. And if Rachel and children lived elsewhere prior to 1763, it would appear that James Hamilton was considered a resident of St. Eustatius starting in 1759 until his move to St. Croix in 1765. Even after that, James continues to appear in the census and may have returned to St. Eustatius after June 1766. If James lived on St. Eustatius prior to 1763 and after June 1766, it is not clear how much time he actually spent on the island during each of those years.

While all this is quite complicated and much remains uncertain, it is clear that James Hamilton, Rachel Faucett Lavien Hamilton, and their two sons spent a considerable amount of time on St. Eustatius in the years 1753 and 1756–1765, as previously shown in Discovering Hamilton and this lecture and now also according to the St. Eustatius censuses.

This extended stay on St. Eustatius raises other interesting possibilities. As a commercial island controlled by the Netherlands, the most common language was Dutch with English and French also being spoken around the town. With Alexander Hamilton being on St. Eustatius in the years 1756, 1757, 1758, and 1763–1765, and perhaps for the intervening years as well, he must have become quite fluent in both Dutch and French as he heard them spoken every day. We knew that Hamilton was fluent in French, but his fluency, or at least familiarity, with Dutch was, as far as I know, not previously mentioned by anyone.

© Posted on July 26, 2021, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

Interesting and informative; thanks for all the work you put into these!

Interesting and unsettling as well… it must have been a sport to avoid the taxes. I wonder if the head taxes were quite different per island (a Dutch island versus a Danish island) and how much they paid per slave? Did they pay more for a grown slave then for a child slave? And would they pay more head tax for a male slave than for a female slave?

Thank you again for this great breakdown of the facts! Your research is extraordinary.

It appears that the head tax, in this case, was not on the slaves owned but rather on the household and the number of white adult males (or females if there was no male head of household). Surely there was also a tax on slaves, but this was a census not a tax book. (In contrast, the St. Croix matrikels were primarily tax and property records and only secondarily censuses.)

Your extensive, laborious research is greatly appreciated. It is wonderful to have all this new information to combine with your book which I treasure. Also, we should all be grateful that you and the other researchers can read cursive, which is now not being taught in many American schools.