Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

© Posted on December 4, 2017, by Michael E. Newton.

In March 1706, a fleet of about fifty French ships with three to five thousand soldiers descended upon the island of Nevis. With a mere three or four hundred men of fighting age, the vastly outnumbered Nevisians fled into the mountains and the following day capitulated. In violation of the terms of surrender, the French burned down most of the dwelling houses on the estates, many of their boiling houses as well, and about half of Charlestown before they absconded with 3,187 of the island’s 6,023 blacks, in addition to “the greatest parts of our mills and coppers with other rich merchandizes, to the value of a great many scores of thousand pounds.” As a result, “Nevis, which formerly seemed to be the Garden of the Caribbees,” was in “a deplorable spectacle of ruin, her forts demolished, plantations burnt, as well canes as houses, their negroes, some taken, the rest fled to the mountains.” Many inhabitants left the island, “some to New England, Pennsylvania, etc.” According to a petition by the merchants and planters of Nevis and St. Kitts, “The damage done to Nevis, by a modest computation, amounts to a million of money.”[1]

The proprietors and merchants of St. Kitts and Nevis requested half a million pounds sterling from the home government “for the relief of the islands.”[2] Over the next few years, Britain sent “considerable quantities of stores and provisions” to Nevis.[3] In the meantime, “Her Majesty was graciously pleased to appoint commissioners in those islands to compute their losses,” which the commissioners calculated to be £356,926, 10 shillings, and 1 pence. In April 1709, Parliament voted £103,203 11s 4d “for the use of such proprietors or inhabitants only of Nevis and St. Christophers who were sufferers by the late French invasion there and who shall resettle or cause to be resettled their plantations in the said islands.”[4]

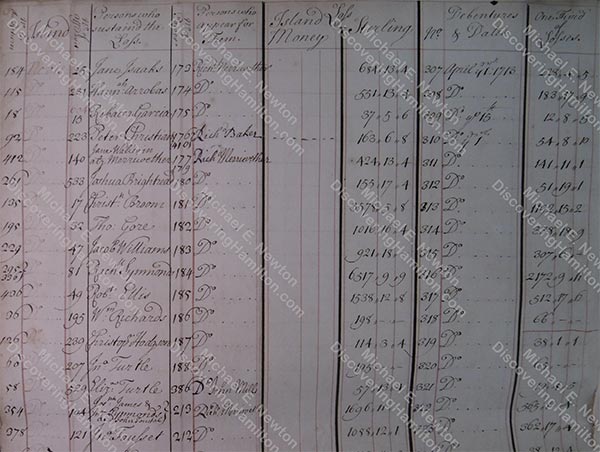

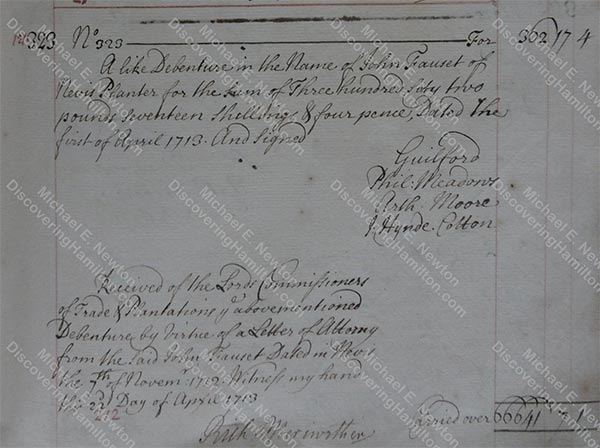

Six hundred sixty-nine people submitted claims for the recovery of “one third of [their] losses” and took “oaths to prove” their “re-settlement” on Nevis and St. Kitts.[5] Among the group was Alexander Hamilton’s grandfather, John Faucett, spelled “Fauset” and “Fausset” in these records, who submitted a claim for a loss of £1,088 12s 1d, more than double the average and about ten times the median claim.[6] In 1713, the Commission for Trade and Plantations started paying these claims and many received their relief funds that year.[7] On April 1, 1713, more than seven years after the French invasion, the Commission for Trade and Plantations issued a debenture, a monetary claim on the government, to John Faucett for £362 17s 4d.[8]

Note: In the first image, John Faucett (“Jno Fausset”) appears in the last line:

* I would like to thank Rhiannon Markless (www.legalarchiveresearch.com) for locating and photographing at my request the above documents within the collections of the U.K. National Archives.

Even with this substantial relief, John Faucett suffered a large loss of £725 14s 9d, by his estimate, more than fifty times the average annual wage of an Englishman.[9] A loss of this magnitude could not easily be recovered.

To be continued…

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries or quoting this blog.

[1] Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, 1706 – June 1708 102, 108–110, 118, 141, 142–144, 146, 147, 180, and 184–185; ibid. June 1708 – 1709 8; ibid. March 1720 – December 1721 119–123. See also “The Case of the Poor Distressed Planters, and other Inhabitants of the Islands of Nevis, and St. Christophers, in America,” published in London, 1709.

[2] Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, 1706 – June 1708 396.

[3] Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, 1706 – June 1708 411; ibid. June 1708 – 1709 91 and 92.

[4] “The Case of the Poor Distressed Planters, and other Inhabitants of the Islands of Nevis, and St. Christophers, in America,” published in London, 1709; The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons from the Restoration to the Present Time 4:63 and 129.

[5] Journal of the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations, February 1709 – March 1715 383–386, 387–388, 292–393, 394–395, etc.; and unpublished documents from the U.K. National Archives not cited for reasons previously explained.

[6] See first image included above.

The 669 claims averaged £439 but the median claim was closer to £100. Most of the claims were for small losses of about £100 or less, but a few very large claims (the largest was for £8,525) skews the average upward.

[7] Unpublished documents from the U.K. National Archives not cited for reasons previously explained; Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, July 1712 – July 1714 283; Journal of the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations, February 1709 – March 1715 406, 408, 410, etc.

[8] See both images included above.

[9] “The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain,” https://www.measuringworth.com/ukearncpi/.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries or quoting this blog.