Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

© Posted on November 27, 2017, by Michael E. Newton.

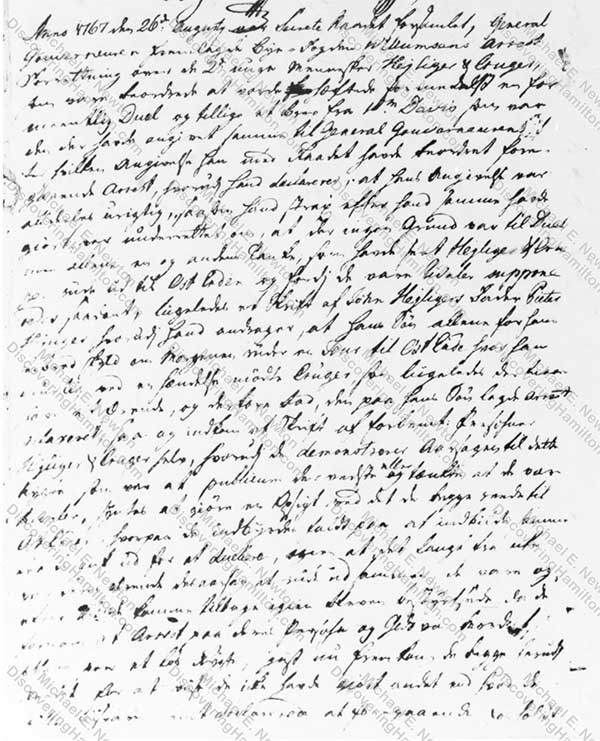

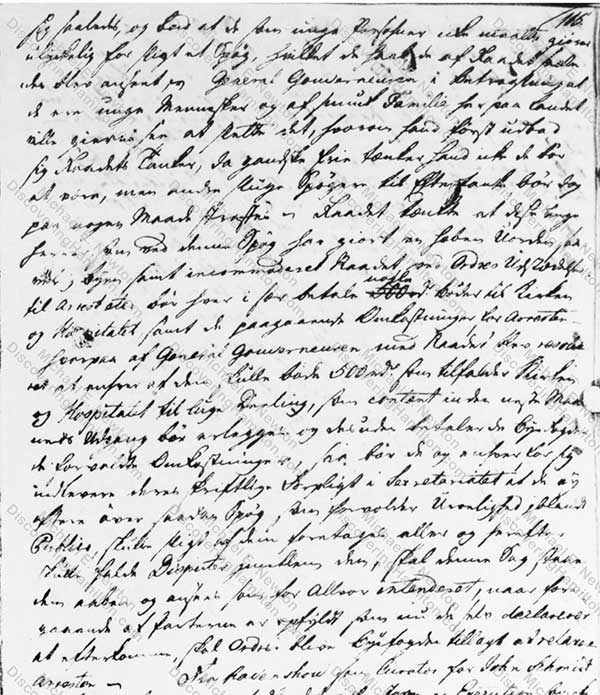

In August 1767, just days after Alexander Hamilton appeared in a legal document alongside his employers Nicholas Cruger and David Beekman, a William Davis informed the governor general that he had seen John Heyliger and Nicholas Cruger “ride out to the East End” to duel “because they were rivals.” The governor general and privy council ordered the sheriff of Christiansted to “arrest” Heyliger and Cruger and take them “into custody because of the supposed duel.”

“Immediately after” he had made the accusation, William Davis was “informed that there were no grounds” to believe that Heyliger and Cruger had gone out to duel except that someone had seen them ride out together and it was “supposed” that they had done so for this purpose. Davis therefore “declared” in a letter to the privy council “that his accusation was completely false.” At the same time, Peter Heyliger, John Heyliger’s father, informed the privy council that his son rode out “solely on account of his health” and “by accident met Cruger, who could likewise have had an errand there.” The senior Heyliger requested that “the arrest put on his son be relaxed.”

When John Heyliger and Nicholas Cruger returned to town and “learned that the arrest of their persons and goods had been ordered solely on account of a groundless rumor,” they wrote to the privy council to explain that “the cause of this rumor…was that the public…thought that they were rivals and so it seemed to cause a sensation that they both rode out to the East End. They therefore both decided to give the impression that they went out to duel, but that this by no means was the reason to ride out together.” John Heyliger and Nicholas Cruger shortly thereafter “appeared” before the privy council “to show that they had not done anything other than what they had written, and declared that the preceding had happened thus. And they asked that they as young persons were not to be made unhappy [i.e., ruined] on account of such a jest.”

The governor general requested that the arrest of Cruger and Heyliger be annulled because they were “young men and of good family here in the country,” but added that he did “not think that they ought to be entirely free, but they should be punished in some measure so that other such jesters might think again.” The privy council decided that due to the “disorder” this had created “in town” and how the privy council was “inconvenienced” by the ordeal, Cruger and Heyliger were each ordered to pay “the incurred costs of the arrests” plus another 500 rigsdalers, “which would go to the Church and the Hospital to share equally.” On top of this, each had to “submit their written promise . . . that they would not in the future make such jest that causes discord among the public.”

* I would like to thank Mads Langballe Jensen (madslangballe@gmail.com) for translating the above document from old Danish into English at my request.

As an employee of Beekman & Cruger and friend to Nicholas Cruger, Alexander Hamilton must have stayed apprised of this affair as it proceeded. Perhaps Hamilton had heard about other duels before, but this is the earliest known case in which Hamilton had a personal interest in the outcome of what he and everyone else believed to be an affair of honor. Of course, no duel took place nor was one ever contemplated, but the rapidity in which the privy council took up this issue and the steep fines assessed against the jesters showed Hamilton that affairs of honor were no joking matter. He would learn this lesson most tragically later in life, but according to the extant records it was here on the island of St. Croix in August 1767 that a ten-year-old Alexander Hamilton first became interested in a “duel.”

Nicholas Cruger’s “supposed duel” also raises the interesting question of what might have happened to Alexander Hamilton had Cruger been put under long-term arrest, been expelled from the island, or, even worse, been killed. Would Hamilton have found another job in the same field? Would Hamilton’s link to mainland North America and specifically to New York City through his employers been severed if Hamilton had been forced to find another job? Would Hamilton have ended up staying in the West Indies and never come to Britain’s mainland colonies? Alexander Hamilton’s life and the future of the United States could have been very different had Nicholas Cruger’s “supposed duel” ended with a more disagreeable result.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries or quoting this blog.