Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

© Posted on February 12, 2018, by Michael E. Newton.

Last week I shared the story of “James Hamelton en Rachel Hamelton desselfs Huysvrouw [James Hamilton and Rachel Hamilton his housewife],” the parents of Alexander Hamilton, serving as godparents on St. Eustatius in 1758 to Alexander Fraser Jr., the son of “Alexander Fraser en Elisabeth Thornton desselfs Huysvrouw [Alexander Fraser and Elizabeth Thornton his housewife].” I also shared some new discoveries regarding how these two families may have known each other prior to this event and how this friendship apparently continued years later on St. Croix.

Now, for the rest of the story.

Alexander Fraser’s Children

As noted last week, Alexander Fraser was living on St. Croix without his family when the Hamiltons arrived in 1765. In his will of 1767, which was also shared last week, Alexander Fraser stated that his wife Elizabeth had already passed away, his daughter Mary Anne was living in North America, and his son Alexander Jr. was in Montserrat. Thus it would seem that Alexander Fraser, after the death of his wife Elizabeth, must have felt that he was unable as a single father to raise his own children. While it was not unusual for parents, especially single parents, to send their children away for an education, here was a man, as a teacher, taking care of and teaching other people’s children but unable or unwilling to care for his own.

After Alexander Fraser’s death in April 1767, letters arrived from his children or their representatives addressed either to the dead father or to the estate.

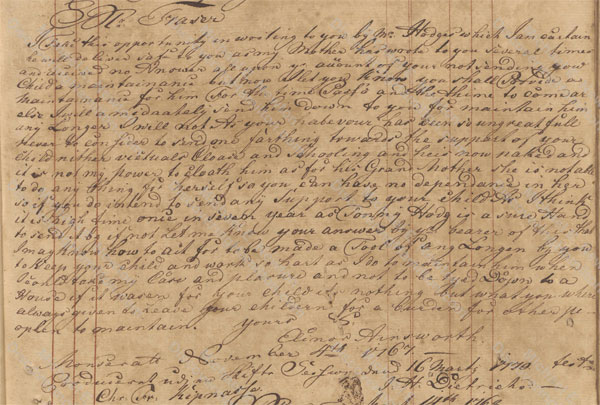

In November 1767, an Elinor Ainsworth from Montserrat wrote to Alexander Fraser, unaware that he had passed away seven months earlier, to complain that she and her mother had written to him “several times and received no Answer.” They wanted to know why he had not sent “a maintenance” to his “child,” i.e., Alexander Fraser Jr. She threatened to “send him down” to rejoin his father in St. Croix because she could not “maintain him any longer.” She chastised Alexander Fraser for being “so ungrateful” for never sending even “one farthing” for his son “in seven years,” “neither victuals, clothes, and schooling,” leaving the boy entirely “naked.” Moreover, the boy’s grandmother, probably Elizabeth Thornton’s mother, was “not able to do anything for herself” and therefore the child “can have no dependence in her.”[1]

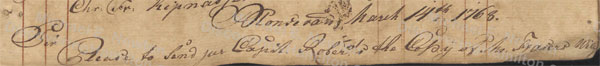

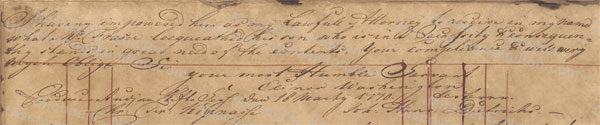

By March 1768, Elinor Ainsworth, now Elinor Washington, learned that Alexander Fraser had passed away. She hired an attorney, a Captain Roberts, to get a copy of the will and to collect “what Mr. Fraser bequeathed his son,” who “stands in great need of the contents.”

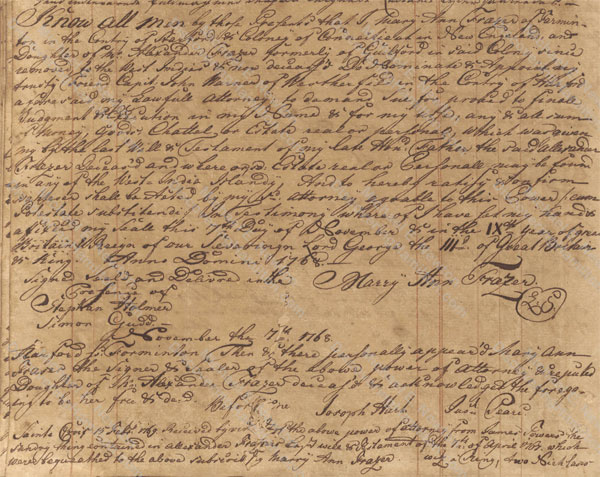

In November 1768, “Mary Anne Frazer” wrote from “Farmington in the Country of Hartford & Colony of Connecticut in New England” describing herself as the “daughter of Mr. Alexander Fraser formerly of Guilford in said Colony since removed to the West Indies & now deceas’d.” Mary Anne appointed a Captain John Warner of Wethersfield to be her attorney to collect her portion of Alexander Fraser’s estate. According to the probate record, John Warner in February 1769 collected Mary Anne’s inheritance, namely “a Ring, two Necklaces, and Six Tea Table Spoons & Tea Tongs of Silver.” Presumably, Mary Anne also received the “five hundred acres of Eastward Land” in North America that her father left to her in his will.

This explains the whereabouts and conditions of the two children that Alexander Fraser mentioned in his last will and testament. However, he had at least one other child, to whom he left nothing and failed to even mention in his will.

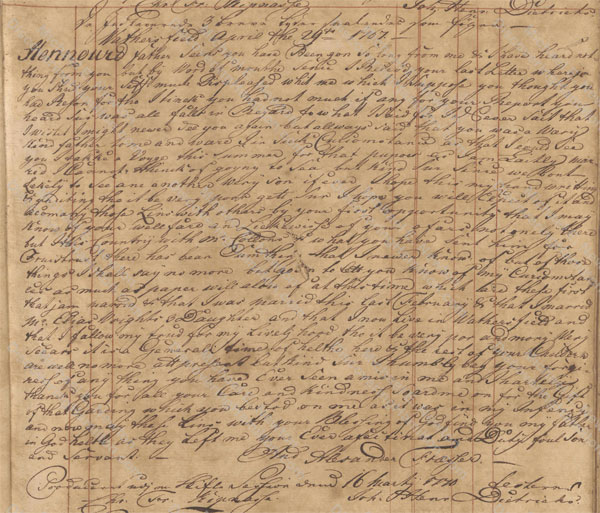

On April 29, 1767, an Andrew Alexander Fraser wrote from Wethersfield, Connecticut, to his father, of course not knowing he had passed away just two weeks earlier. Andrew Alexander noted that it had been some time since he had heard from his father and supposed that this was the result of his father being “much displeased” with him after having received a “false” report about something he had said. Andrew Alexander assured his father that he “never said that I wished I might never see you again but always said that you was a very kind father.” After expressing his wish to see his father again, Andrew Alexander informed him “that I am married & that I was married this last February & that I married Mr. Elias Wright’s 3[rd] Daughter and that I now live in Wethersfield.” Andrew Alexander added that despite this happy occasion his “livelihood” was “very poor.” He also told his father that “the rest of your Children are well.” Andrew Alexander closed by “humbly beg[ging] your forgiveness of anything you have ever seen amiss in me and I heartily thank you for all your care and kindness toward me and for the Gift of that Guarding which you bestowed on me as it was in my Infancy.”

Perhaps if this letter had reached Alexander Fraser before he passed away, he would have also bequeathed something in his will to his son Andrew Alexander.

Alexander Fraser’s Early Family Life in Connecticut

According to the above letter, Andrew Alexander married in 1767, suggesting he had been born prior to 1750, when Alexander Fraser was still residing in Connecticut. It would thus appear that Alexander Fraser had a wife in Connecticut before moving to the West Indies. Assuming that Elizabeth Thornton was from the West Indies, as the Thorntons on Nevis and Alexander Fraser Jr.’s grandmother on Montserrat would suggest, it is likely that Alexander Fraser had these children with a first wife in Connecticut, she died, he then moved to the West Indies, and there married Elizabeth Thornton.

Elizabeth Thornton’s Death

Unfortunately, there is no record of what happened to Alexander Fraser’s wife Elizabeth Thornton except that she died before Alexander Fraser made out his will in April 1767. Based on the above letter from Elinor Ainsworth, which states that she and her mother had been taking care of Alexander Fraser Jr. without support for seven years, it would appear that Alexander Fraser sent his children away in 1760, which also happens to be the same year he first appears in the records of St. Croix (specifically March 1760, though he does not appear in the census and property records until January 1765). This would suggest that Elizabeth Thornton passed away at that time (1760) or shortly beforehand (perhaps in 1759), at which time Alexander Fraser shipped off his children to live with friends or relatives.

But this still leaves several questions unanswered. Were Alexander and Elizabeth Fraser still living on St. Eustatius when Elizabeth passed away? Were the Hamiltons also there when Elizabeth Thornton Fraser died? Did they attend the funeral? Unfortunately, no records have been found regarding Elizabeth Thornton Fraser’s death and burial (the burial records of St. Eustatius’s Dutch church, where Alexander Fraser Jr. was baptized, are badly damaged) or when the Hamiltons left St. Eustatius.

The Friendship of Faucetts, Hamiltons, Thorntons, and Frasers

The only record of a friendship between the Faucetts and Hamiltons on the one side and the Thorntons and Frasers on the other is the 1758 baptism of Alexander Fraser Jr., where James and Rachel Hamilton served as godparents. But the numerous times that these families’ paths intersected suggest that this was more than just a short, one-time friendship. For decades, the Faucetts lived alongside the Thorntons in St. George’s Parish, Nevis, and Elizabeth Thornton may have belonged to this family. When the Hamiltons move to St. Croix, Alexander Fraser happened to be living there just blocks away.

Travelling from island to island—James Hamilton and Rachel Faucett lived on at least four different islands together—one might think that they had to make new friends in each location. The fact that someone could run into old friends on a new island shows how common it was for people to move between the various islands. Moreover, large waves of migration from one island to another often occurred. As a result, when a family moved from one island to another, it was common for other family members or friends to do so around the same time. (One such migration that played a large role in the Faucett–Hamilton narrative was the large exodus of people from St. Kitts and Nevis to St. Croix that began in the 1730s.) Thus, when moving from one island to another, one could expect to meet old friends there.

The Hamiltons On St. Eustatius

It is unlikely that James and Rachel traveled to St. Eustatius just to attend the baptism of the son of Alexander and Elizabeth Fraser, even if they were close friends or relatives. More likely, their trip was related to Mary Faucett, Rachael’s mother, who had been living on St. Eustatius and died sometime after May 1756, leaving three slaves to her “beloved daughter, Rachael Lavion.”[2] Or perhaps James had been sent to St. Eustatius by his employer, just as he would be sent to St. Croix in 1765. In the end, we don’t know why James and Rachel went to St. Eustatius, but the one extant record shows that they were treated there like a normal married couple.

All this raises the question of how much time the Hamiltons spent on St. Eustatius. Even those few who have chosen to write about the Hamiltons on St. Eustatius, including myself in Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years,[3] make it sound like they were there for a short visit. In reality, we don’t know how long they stayed on the island. The only evidence we have regarding the whereabouts of the Hamiltons between the birth of Alexander in January 1757 and their arrival on St. Croix in the spring of 1765 is this one record putting them on St. Eustatius in October 1758. They could have been on the island of St. Eustatius for days, weeks, months, or even years. If some piece of evidence is found to answer this question, it could significantly change the narrative of Alexander Hamilton’s life.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

Endnotes

[1] It is possible that Alexander Fraser Jr.’s grandmother and Elinor Ainsworth’s mother are the same person. If so, Elinor Ainsworth was the sister of Elizabeth Thornton.

[2] Atherton, “The Hunt for Hamilton’s Mother” 237–238; H. U. Ramsing, “Alexander Hamilton og hans Mødrene Slaegt”; Mitchell, Alexander Hamilton: Youth to Maturity 8 and 478 note 4.

[3] Newton, Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years 17.

© Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.