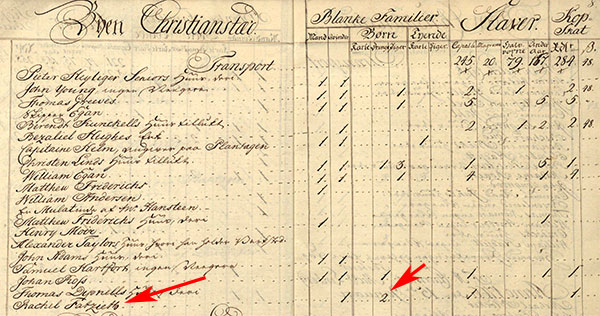

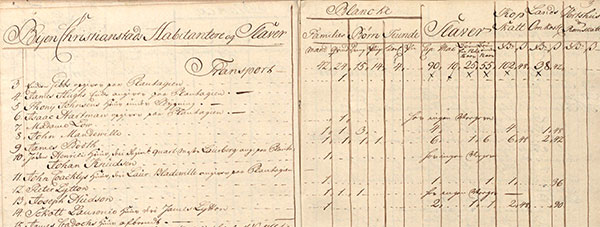

When the Hamiltons moved to St. Croix in 1765, James Hamilton Jr. and Alexander Hamilton lived with their mother Rachel Faucett Lavien [Hamilton]. This is can be seen in St. Croix matrikels [censuses] of 1765–1767 where Rachel Fatzieth/Lewin is listed as living with two sons.

After Rachel’s death, James Jr. and Alexander Hamilton are not listed in St. Croix’s matrikels. Presumably they were counted elsewhere in the matrikels, but they were not named. With whom did they live? Were they counted as children in someone else’s household, as adults, or as white servants?

James and Peter Lytton

It appears that after Rachel’s death, Peter Lytton became the guardian of the Hamilton boys. The probate record for Rachel’s estate states, “Present for the two minor children and heirs was Mr. James Lytton on behalf of Peter Lytton, who is a son of the minor children’s mother’s sister.”[1]

Thus, Peter Lytton, a first cousin of the Hamilton boys, apparently became their guardian when Rachel died. Logically, the Hamiltons would have gone to live with him. However, for some reason, Peter did not attend the probate court on February 22, 1768. Instead, James Lytton, the Hamiltons’ uncle, represented them. Perhaps James Jr. and Alexander went to live with James Lytton instead.

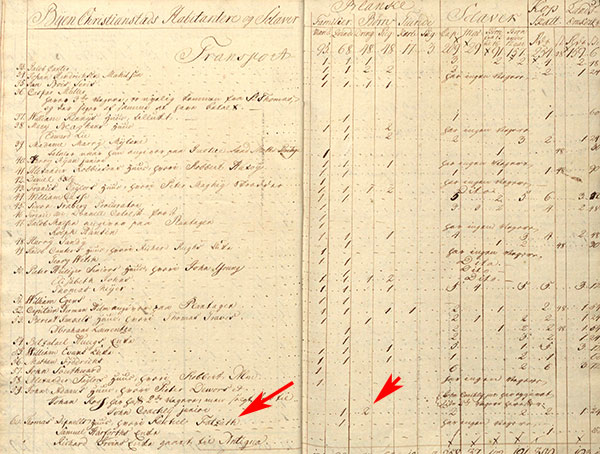

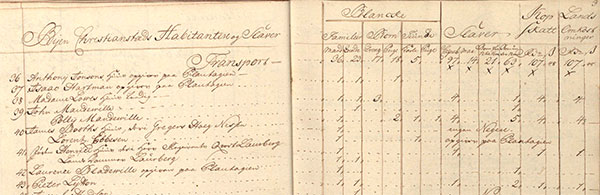

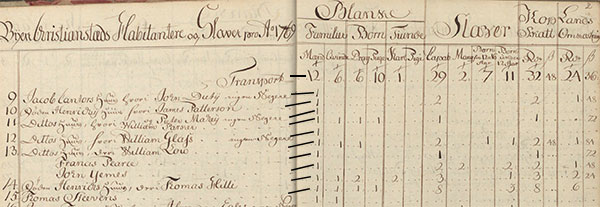

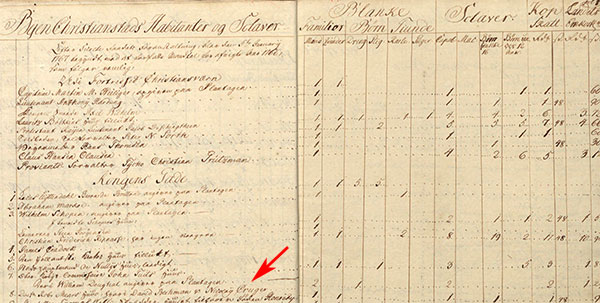

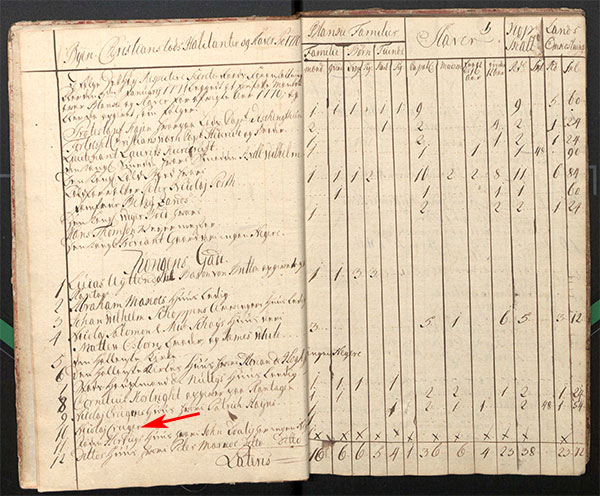

As of January 1768, about a month before Rachel’s death, Peter Lytton resided at 12 Kongens Gade (King’s Street) and James Lytton at 14 Kongens Gade. Each one lived by himself, besides a few slaves.

The following year, in January 1769, Peter Lytton was at 43 Kongens Gade (King’s Street), which was the same house as the year before even though the numbering was reorganized in the interim, and James Lytton had moved to 21 Strand Gaden (Beach Street). They are again living alone, besides slaves. (Both James and Peter Lytton died in August 1769, so there are no future matrikels to check.)

It is therefore clear that the Hamilton boys were not living with James or Peter Lytton as of January 1769. Perhaps they had moved in with one or the other when their mother died, but if so they must have moved out before the end of 1768. Perhaps they spent just a few days with James or Peter Lytton before finding more permanent housing. Or perhaps they never lived with either Lytton. Perhaps they immediately went to live with friends or their employers (more about these possibilities later).

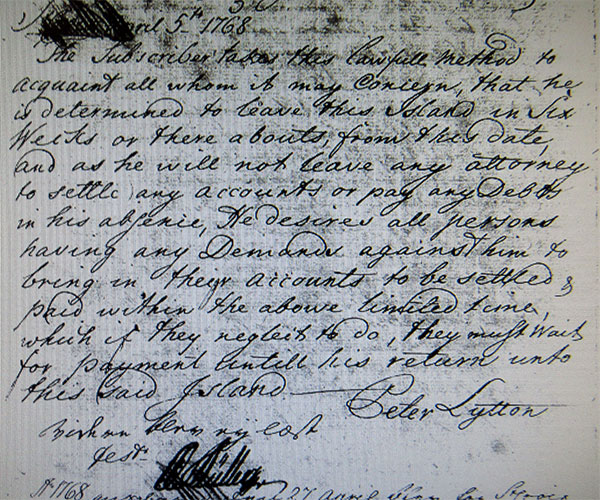

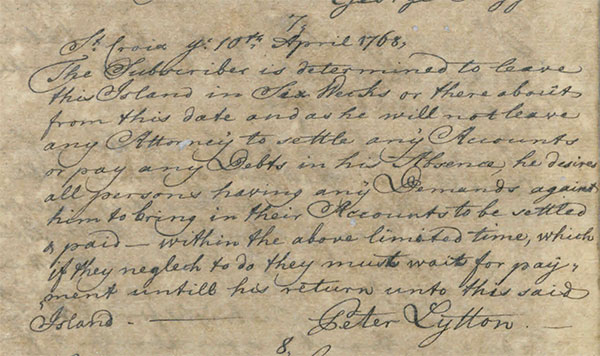

If the Hamilton boys initially moved in with their guardian Peter Lytton, perhaps they left his house when he announced on April 5, 1768,[2] and again on April 10, that he was “determined to leave this island in six weeks or thereabouts” and requested “all persons having any demands against him to bring in their accounts to be settled & paid within the above limited time.” Also of note is that Peter Lytton declared that he would “not leave any attorney,” so it is not clear who would become guardian to the Hamilton boys in his absence. Perhaps James Lytton took on the job.

No record has been found as to whether Peter Lytton left St. Croix in May 1768 as planned and if so for how long, but he was on St. Croix in August 1768[3] and possibly in July[4] and is found again on St. Croix in September[5] and October.[6]

There is no evidence that the Hamiltons ever lived with either James or Peter Lytton, but it is possible they had immediately after their mother’s death, but they certainly were no longer living with either of them as of January 1769 and if they had moved in with their guardian Peter Lytton it is likely they left his house in May 1768 when Peter was supposed to have left St. Croix.

Thomas Stevens

It has been argued that Alexander Hamilton and perhaps James Hamilton Jr. lived with Thomas Stevens.

There is some reason to believe that the Hamiltons did indeed live with Stevens. In 1822, Timothy Pickering, who knew both Alexander Hamilton and Edward Stevens, wrote, “To-day, Mr. Yard informed me…that when young children, they [Alexander Hamilton and Edward Stevens] lived together in the family of the father of Stevens, and were sent together to New York for their education.”

Thus, we have a relatively reliable source saying that Alexander Hamilton lived with the Stevens family. Since Edward Stevens went to New York for his education, probably in the summer of 1769,[7] Alexander Hamilton must have lived with the Stevens family in 1768 or the first half of 1769, if Pickering’s account is correct. But notice that Pickering thought that Hamilton and Stevens “were sent together to New York for their education.” This was not the case. Stevens went to New York probably in the summer of 1769 and entered King’s College in 1770 whereas Hamilton went to New Jersey in 1772, started studying at King’s in 1773, and officially matriculated in 1774. With Pickering wrong about that detail, it’s possible he was mistaken about the other.

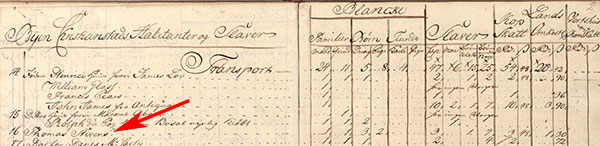

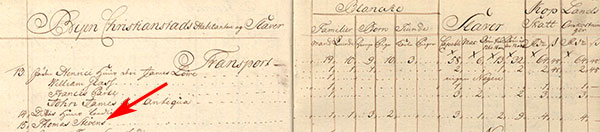

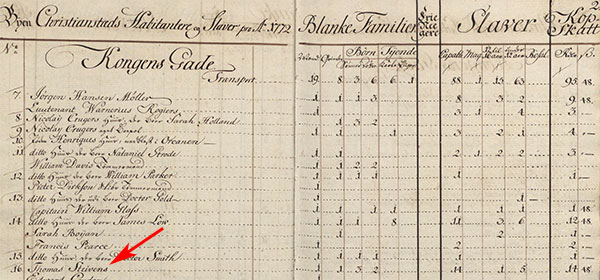

Others have looked at St. Croix’s matrikels and supposedly determined from these that one or both of the Hamilton children moved in with the Stevens family. For example, William Cissel wrote that “Stevens had 3 sons and 2 daughters” and the “1769 Landlist for their residence tallied that number of boys in the family” along with two white male servants, “possibly both Hamilton brothers, taken in after the death of Peter Lytton.” He then points out that “the 1772 register shows 3 white boys in the family but no white servants, so Alexander Hamilton may have been ‘upgraded’ in relationship. His brother James was living elsewhere.”[8] Others, including myself, have since repeated these assertions.[9]

Unfortunately, Cissel erred in his reading of the matrikels and it appears that the Hamiltons did not live with the Stevens or, if they did, as Timothy Pickering said, it must have only been for a short time.

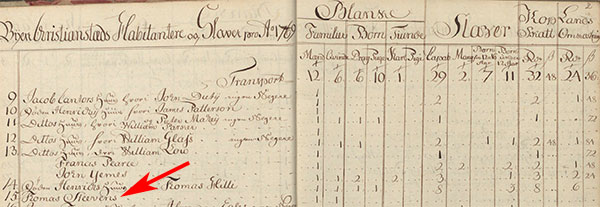

In the 1767 matrikel, compiled in January 1768, when the Hamiltons were still living with their mother, the Stevens household consisted of Thomas Stevens, his wife Ann, three sons, and two daughters. These five children were presumably the Stevens children—Thomas, Edward, Richard, Mary, and Ann (according to Thomas Stevens’s 1778 will). These numbers gives us a reference for future counts.

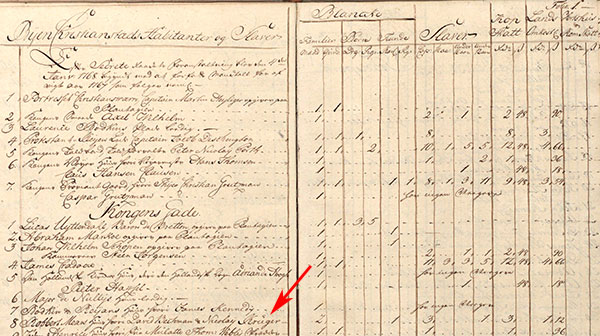

In the 1768 matrikel, compiled in January 1769, the Stevens household again has one man, one woman, three male children, two female children, and no white servants. Assuming that the children are the Stevens children—and there is no evidence that any of the Stevens children had left St. Croix before this date as it appears that Edward Stevens left in the summer of 1769, as mentioned earlier—then the Hamiltons were not living in the Stevens household at this time.

However, Thomas Stevens Jr. was older than Edward Stevens, so perhaps he had left St. Croix to pursue his education. If so, one of the three sons could have been Alexander Hamilton. But there is no evidence to support this.

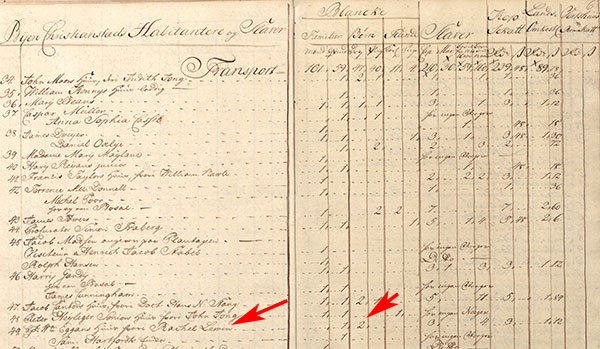

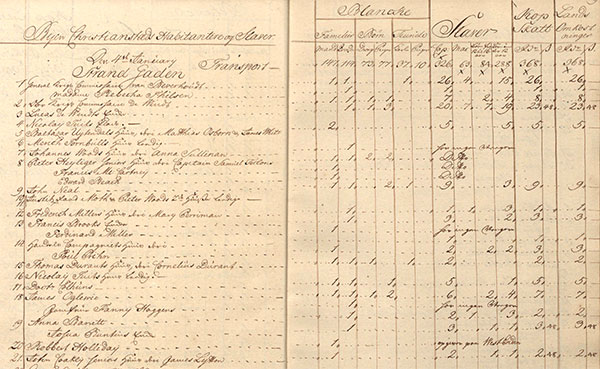

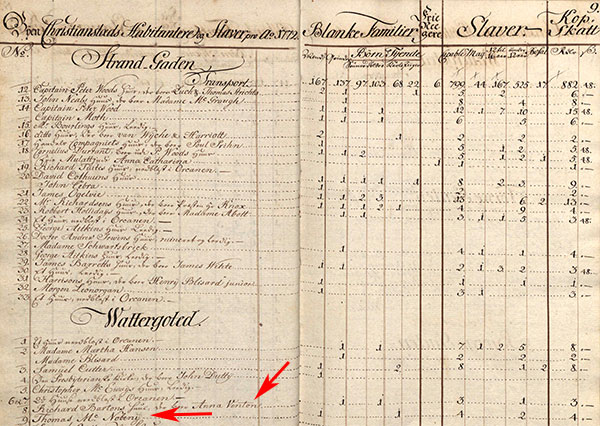

Things change in the Stevens household in the 1769 matrikel, compiled in January 1770. Rather than seeing an increase in the number of people in the household, which would have been the case if one or both of the Hamilton boys had moved in, there is instead a decrease in the number of people in the household as Edward Stevens leaves St. Croix for New York and perhaps others of the children did the same or went somewhere else. In addition to Thomas Stevens and his wife, there are now just one son and one daughter counted. Again, there were no white servants in the household.

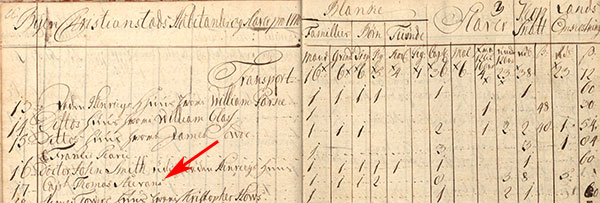

This is the matrikel that Cissel pointed to in saying that there were three boys counted along with two white male servant. The lines in this matrikel are hard to align, but there are none in which three boys and two white servants can be found. The line for Thomas Stevens has, as mentioned, one boy, one girl, and no white servants. (I have added lines to a second image to help align the counts with the individuals.) Thus, according to the official census takers, the Hamiltons were not living with the Stevens family in January 1770.

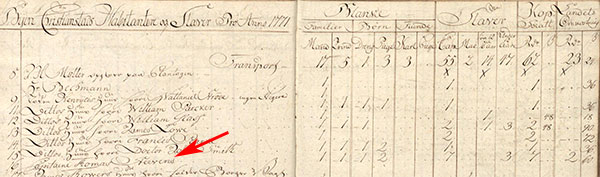

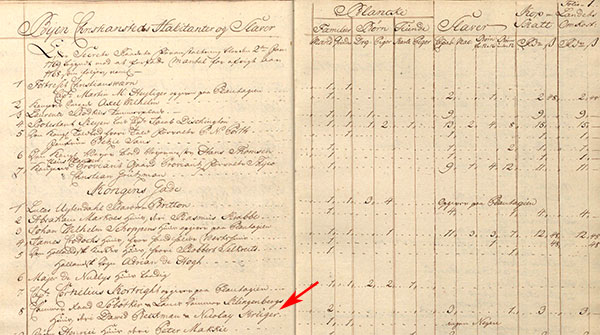

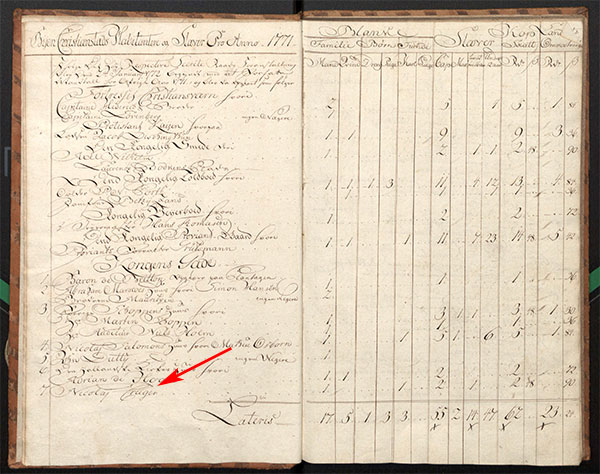

In the 1770 matrikel, compiled in January 1771, the household of “Capt Thomas Stevans” included one man, one woman, one boy, and two girls. There are the same number of boys in the household as in January 1770 but one of Stevens’s two daughters had returned. No white servants are counted in the household and thus no Hamiltons were living with Stevens.

The 1771 matrikel, compiled in January 1772, shows the same numbers for the household of “Capitaine Thomas Steevens,” namely one man, one woman, one boy, two girls, and no white servants. Yet again, these children are, presumably, the children of Thomas Stevens, and the Hamiltons were not living with the Stevenses.

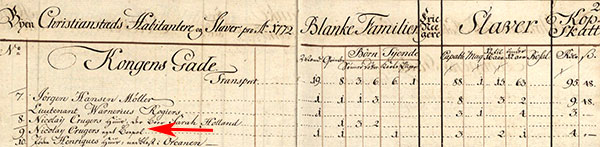

According to the 1772 matrikel, compiled in January 1773, the household of “Thomas Steivens” had one man, one woman, three sons, and two daughters, an increase of two boys from the previous year. Edward Stevens was still in New York but perhaps the other son who had fallen off the census in January 1770. That still leaves one boy whose identity remains unknown. Alexander Hamilton by this time was gone, so the extra boy could not have been him.

William Cissel had written that “the 1772 register shows 3 white boys in the family but no white servants, so Alexander Hamilton may have been ‘upgraded’ in relationship. His brother James was living elsewhere.”

But we have already seen that there were never any white servants in the Stevens household according to the matrikels, so Alexander Hamilton could not have been “upgraded” from a servant to a male child.

Also, Cissel thought, based on some receipts and previous biographers, that Alexander Hamilton did not leave St. Croix until 1773.[10] Indeed, there had been some debate over when Hamilton left St. Croix, but I have since proven that Alexander Hamilton left St. Croix in September or October 1772.[11] So the extra boy appearing in the matrikel in the Stevens household could not have been Alexander Hamilton.

Thus, St. Croix’s matrikels never show the Hamiltons living with the family of Thomas Stevens. Timothy Pickering wrote that “they [Alexander Hamilton and Edward Stevens] lived together in the family of the father of Stevens,” so this cannot be discounted. But if Alexander Hamilton did live with the Stevens family, it would have been for a period of months in between matrikel compilation dates or perhaps in 1768–1769 if the oldest Stevens boy left St. Croix and was replaced in the 1768 matrikel by Hamilton, rather than years 1769–1773 as Cissel asserted. If Alexander Hamilton did live in the Stevens household, he probably moved out when Edward Stevens departed St. Croix in or before the summer of 1769.

Nicholas Cruger

Another possibility is that Alexander Hamilton went to live with his employer Nicholas Cruger after his mother died.

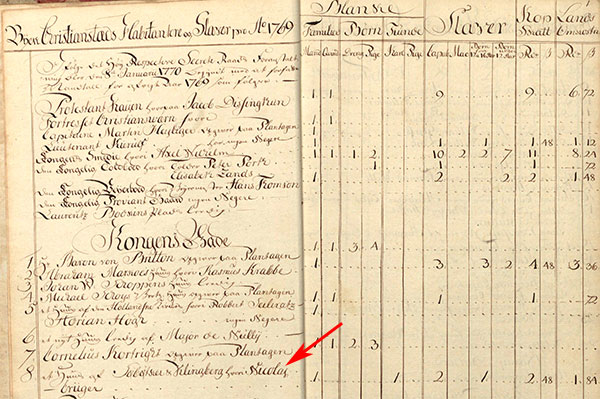

According to the 1766 matrikel, compiled in January 1767, David Beekman and Nicholas Cruger had two men and one male child living at the address of their mercantile operation. The two men were Beekman and Cruger, but who was the boy? Perhaps it was a young clerk employed by the company. Alexander Hamilton, who started working for Beekman and Cruger in 1766 or very early 1767,[12] may have already been working for the company when the matrikel was compiled, but he was still living with his mother so this can’t be him. Another possibility is that one of the two partners had become guardian to an orphan.

The 1767 matrikel, compiled in January 1768, shows something slightly different. Beekman and Cruger are both counted in the census but instead of having one male child with them they have one white male servant. It very well could be the same person, i.e., a clerk who worked for the company. Alexander Hamilton was definitely working for Beekman and Cruger by this time, but he and his brother were still living with their mother.

According to the 1768 matrikel, compiled in January 1769, the first in which the location of the Hamilton children is not known, Cruger and Beekman are still living at their business address but no children or white servants are found with them.

The 1769 matrikel, compiled in January 1770, shows Nicholas Cruger still at that same location but David Beekman had left (other evidence shows that they dissolved their partnership). One white male servant is also found with Cruger. Could this be Alexander Hamilton? Or another clerk? Perhaps the same one from the 1767 matrikel?

The situation was the same the following year. In the 1770 matrikel, compiled in January 1771, Nicholas Cruger is found at his business with one white male slave. (The previous line is unrelated to our story. It states, “Nicolay Crugers huus hvori Patrick Hayns [Nicholas Cruger’s house, wherein Patrick Hayns],” indicating that this was a house owned by Cruger but occupied by Patrick Hayns [Haynes?])

The 1771 matrikel, compiled in January 1772, again shows Nicholas Cruger with one white male servant. Interestingly, Nicholas Cruger was in New York when this census was conducted, but he had only left temporarily and the property and slaves were still his. He still owed taxes on these and therefore it seems that Cruger was counted despite being absent. Alternatively, it could be a different adult male at the address, perhaps Hamilton, and someone else as the white male servant, all listed under Cruger’s name since he owned the building and the slaves.

The 1772 matrikel, compiled in January 1773, by which time Alexander Hamilton had left St. Croix, shows Nicholas Cruger along with one woman, i.e., his new wife Anna de Nully, who he married in April 1772, along with one white male servant. (The text reads “Nicolay Crugers eget boepol [own residence].”) If this is the same white male servant as in previous years, it could not be Hamilton. But with Hamilton leaving St. Croix in September or October 1772, Cruger would have had to replace him a new clerk, so perhaps it was Hamilton in previous years and this was his replacement. (A white male servant appears in subsequent matrikels as well. In the 1774 matrikel, there is also a white female servant, but not in the years that follow.)

Yet again, the matrikels are not clear as to whether or not Alexander Hamilton lived with Nicholas Cruger, but it is a possibility.

To summarize, David Beekman and Nicholas Cruger lived at their warehouse and store on Kongens Gade (King’s Street) in January 1767, 1768, and 1769, and Nicholas Cruger continued to live there after the partnership between them was dissolved. There was a white male servant living at Nicholas Cruger’s business along with the owner in January 1770, 1771, and 1772, when Hamilton’s living arrangements are not know. As an employee of Nicholas Cruger who spent most of his days at work, it would have made sense for Alexander Hamilton to live at the business location just like his boss. Moreover, Hamilton managed the company for several months in 1771–1772, so it would make even more sense that he lived at headquarters, as his boss had done, during his management of the firm. The 1771 matrikel was compiled during this time when Hamilton managed the company, so the white man or the white male servant could very well be Hamilton.

However, Beekman and Cruger had a male child with them in January 1767 and a white male servant in January 1768, neither of which could have been Hamilton since he was still living with his mother. Also, Nicholas Cruger had a white male servant living with him in the years after Hamilton left St. Croix. Perhaps the white male servant of 1770–1772 was one of these two people. Or perhaps they were clerks just like Hamilton and each was counted in the year they lived at the business.

Accordingly, there is no evidence regarding the identity of that extra person living with Nicholas Cruger in 1770–1772. It is possible that it was Alexander Hamilton, but it could have just as easily been someone else.

Thomas McNobney

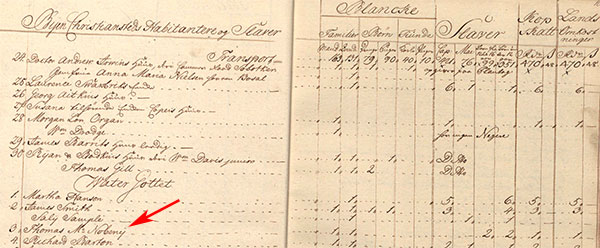

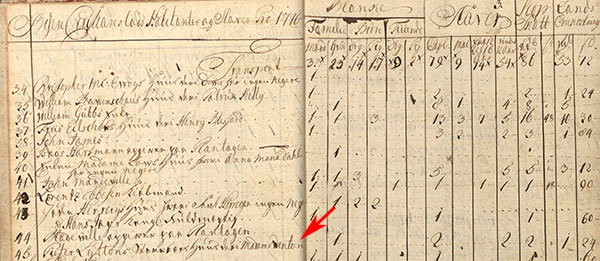

While Alexander Hamilton went to work for Nicholas Cruger in 1766 or very early 1767, James Hamilton Jr. started to apprentice for the carpenter Thomas McNobney sometime prior to July 1769.[13] Perhaps James Hamilton Jr. lived with McNobney. Let’s look at the matrikels to see if this is possible.

Thomas McNobney had no children or servants living with him in January 1769, 1770, 1771, or 1772, but starting in 1773 he had one male servant living with him (he had one male servant living with him in January 1773 and January 1774, two male servants in January 1775 and January 1776).

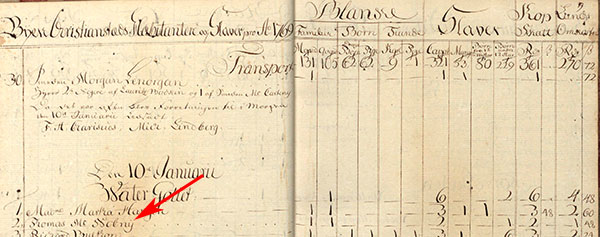

1768 matrikel, compiled January 1769:

1769 matrikel, compiled January 1770:

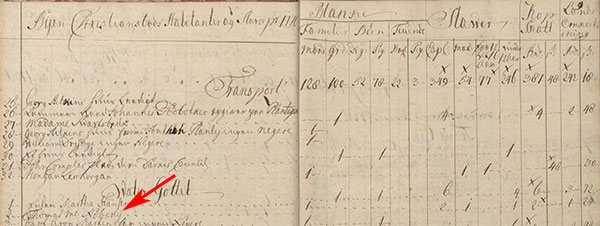

1770 matrikel, compiled January 1771:

1771 matrikel, compiled January 1772:

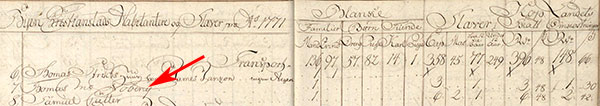

1772 matrikel, compiled January 1773:

Perhaps this white male servant who joined Thomas McNobney in 1772 or January 1773 was James Hamilton after his brother left St. Croix. If so, it would suggest that James and Alexander lived together until Alexander left St. Croix in September or early October 1772. But since it cannot be known whether this white male servant was indeed James Hamilton, we cannot draw any definitive conclusions from it.

Anne Lytton Venton

Anne Lytton Venton[14] was Hamilton’s first cousin, the daughter of James Lytton. She is the one who paid for Alexander Hamilton’s education at the grammar school in Elizabethtown and at King’s College in New York City.

When Rachel died in February 1768, Anne lived in New York. When James Lytton died in August 1769, Anne decided to return to St. Croix to collect her inheritance and she was back on the island by January 22, 1770.[15] This was too late to appear in the 1769 matrikel, which was compiled earlier in the month.

As far as is known, Alexander Hamilton had never met Anne Lytton Venton since she had left St. Croix for New York before the Hamiltons arrived. Hamilton and his cousin soon became good friends, close enough for Anne to pay for Hamilton’s education and for Hamilton to later tell his wife that Ann Lytton Venton was “the person in the world to whom as a friend I am under the greatest Obligations.”[16]

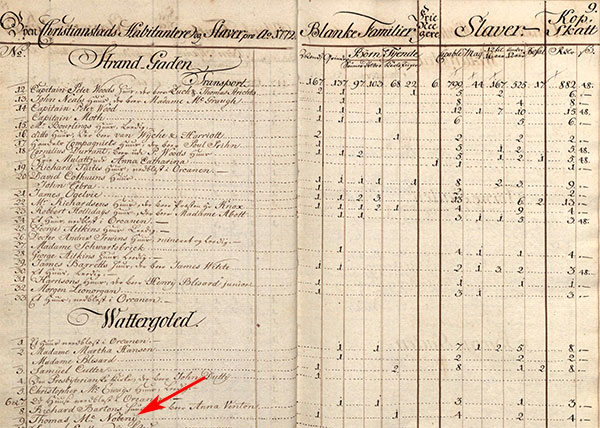

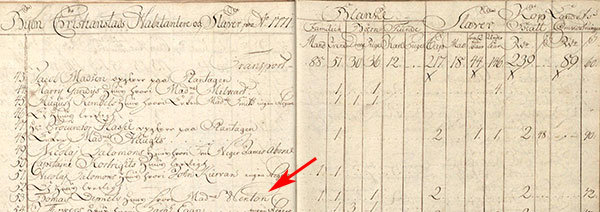

“Madame Venton” first appears in the 1770 matrikel, compiled in January 1771, by herself in “Pieter Lyttons stervboe huus [Peter Lytton’s estate’s house].” This is strange because she had a husband, John Kirwan Venton, and a daughter, also named Anne Lytton Venton. Later evidence suggests that Anne had left her husband. But where is her daughter? Did she leave the daughter in New York with her husband?

The following year, in the 1771 matrikel, compiled in January 1772, “Madame Venton” appears, but this time with one man and one girl in “Thomas Dipnels huus [Thomas Dipnall’s house.” The girl presumably is Anne’s daughter, but who is the man? It is unusual to have a man counted at a residence but the woman listed as the occupant. Usually, the man of the house is the one named. Accordingly, this cannot be John Kirwan Venton. Could it be James or Alexander Hamilton?

Even more interesting is that Ann Lytton Venton was living in one of two houses that Thomas Dipnall owned on Compagniets Gade (Company’s Street), apparently the same house that Rachel, James Jr., and Alexander Hamilton had lived in a few years earlier.[17] What a coincidence! Or perhaps not.

The following year, in the 1772 matrikel, compiled in January 1773, “Anna Venton,” now in “Richard Bartons huus [Richard Barton’s house],” is counted along with one girl, probably her daughter. The man is now gone. If the man the previous year had been Alexander Hamilton, he of course left St. Croix in September or October 1772. If it had been James Hamilton Jr., perhaps he moved to Thomas McNobney’s house, as mentioned earlier.

It is also noteworthy that Anne Lytton Venton now lived next door to Thomas McNobney. It is quite a coincidence, or perhaps not, that James Hamilton Jr. was an apprentice to Anne Lytton Venton’s next-door neighbor. (Was James still McNobney’s apprentice? We do not know when James’s apprenticeship began or ended.)

Here is yet another place Alexander Hamilton may have lived after his mother died but before he left St. Croix. The unnamed adult male with Anne Lytton Venton in January 1772 could be Alexander Hamilton, James Hamilton Jr., or perhaps someone else entirely. Either way, the apparent close relationship between Alexander Hamilton and his cousin Anne Lytton Venton suggests that Hamilton probably spent a considerable amount of time with her, especially since she apparently lived for a time in the house he previously occupied prior to his mother’s death and at another time lived in the house next door to where James Hamilton Jr. worked.

Where did Alexander Hamilton live after his mother died?

Where did Alexander Hamilton live after his mother died in February 1768? As seen above, the census data does not give a clear indication and nothing else has been found to give a definitive answer to this question.

It is possible, perhaps likely, that the Hamilton boys went to live with their uncle James Lytton or first cousin Peter Lytton when their mother died. If so, they apparently did not stay long because they are not counted in either of their households in the January 1769 census.

Alexander Hamilton may have lived for a time with the family of Thomas Stevens, as Timothy Pickering noted, and perhaps James Hamilton Jr. also lived with them, but if this is the case it would not have been for long since they are not found in any censuses with the Stevenses and Edward Stevens left St. Croix by the summer of 1769 and at that time Hamilton would have moved on to another location.

Perhaps Alexander Hamilton lived with his employer Nicholas Cruger. There was a white male servant living at Nicholas Cruger’s business along with the owner in January 1770, 1771, and 1772. If this white male servant was Alexander Hamilton, where was his brother James?

An adult male lived with Anne Lytton Venton in January 1772. This could be Alexander or James Hamilton, or neither of them.

A white male servant is found living with Thomas McNobney for the first time in January 1773. This could be James Hamilton Jr., who apprenticed for McNobney, though it is not known if he was still working for him at this time.

Of course it is also possible that James and Alexander Hamilton took lodgings with someone else, renting a room, without being counted in the matrikel, as their father had done.

As a historian, I am not one to invent narratives without evidence, but in this case, where all the evidence is circumstantial (except the statement by Timothy Pickering), I will propose a plausible answer to question of where did Alexander Hamilton live after his mother died in February 1768.

Most likely, Alexander and James Hamilton moved in with Peter or James Lytton when their mother died. Evidently it was Peter Lytton who became their guardian but it was James Lytton who represented them in the probate court. This arrangement was apparently temporary as Peter Lytton soon left the island and the Hamiltons are not found with either of them in January 1769.

After leaving the Lyttons, perhaps Alexander Hamilton moved in with the Stevens family. Although the matrikel compiled in January 1769 shows no increase in children in the household, possibly the oldest Stevens boy, Thomas Stevens, had left for his education and Alexander took his place in the census count. If so, James Hamilton Jr. probably went to live with a friend or, since he was older, found lodging for himself.

When Edward Stevens left for New York in the summer of 1769, Alexander Hamilton must have left the Stevens household as well because the matrikel compiled in January 1770 shows only one boy in the household, who was the youngest Stevens son. At this point, Alexander Hamilton may have moved in with his employer, Nicholas Cruger, and lived here until he left St. Croix in September or early October 1772.

Perhaps then it was James Hamilton Jr. who lived with Anne Lytton Venton in January 1772 and then with Thomas McNobney starting in January 1773.

Of course, this is speculation and I would be surprised if this was entirely correct. Nevertheless, each individual part represents my best guess, but it is barely more than a guess, as to where Alexander Hamilton and his brother James Hamilton Jr. lived after their mother died.

Nevertheless, this analysis does correct some previous errors. There is no evidence that Alexander Hamilton lived in the Stevens household from 1769 to 1773 as previously asserted. In fact, this appears to be impossible. This analysis also adds some new possibilities, i.e., that one of the Hamilton boys lived with Anne Lytton Venton. It is also clarifies all the known possibilities, making this topic a little less confusing.

Endnotes

[1] Translation by Solvejg Vahl.

[2] St. Croix Panteprotokoller, 1756–1776. U.S. National Archives, College Park, Maryland, RG55 Entry 825 and M1884 Roll 119.

[3] Christiansted Tingsvidneprotokoller 1767–1770 174v, 175v.

[4] St. Croix Landstinget Justitsprotokol 1767–1770 75v.

[5] St. Croix Landstinget Justitsprotokol 1767–1770 91r.

[6] Christiansted Panteprotokoller 1767–1769 416v.

[7] There is no record of when Edward Stevens went to New York, but it would appear to be shortly before Hamilton wrote him a letter in a November 1769. I have not yet written about my new discoveries on this topic, but Edward Stevens was in New York by August 24, 1769.

[8] William F. Cissel, Alexander Hamilton: The West Indian Founding Father 15 and 32 note 108.

[9] Michael E. Newton, Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years 40.

[10] William F. Cissel, Alexander Hamilton: The West Indian Founding Father 17 and 33 note 117.

[11] Michael E. Newton, Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years 57, 59–60, and 69. See also Michael E. Newton, Discovering Hamilton 196.

[12] Michael E. Newton, Discovering Hamilton 179.

[13] See entry #189 here and here. This list was recorded on July 19, 1769, so James Hamilton Jr. must have started apprenticing for McNobney before that date.

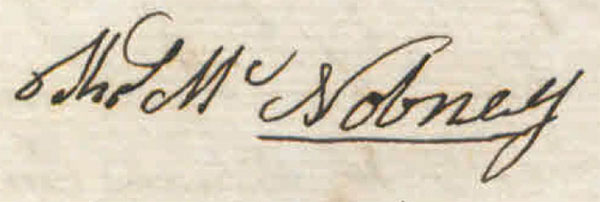

This name has been spelled many way, but his signature reads Thos McNobney (this document with his signature, Thomas McNobney’s 1778 will, has been moved or removed from the Rigsarkivet collection, but I fortunately downloaded it before this happened).

[14] For the spelling of her name as Anne, rather than Ann, see Michael E. Newton, “Anne Lytton Venton Mitchell Records from St. Croix, 1799–1807.”

[15] See entry #1047 here and here.

[16] Alexander Hamilton to Elizabeth Hamilton, July 10, 1804, in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton 26:307. See also Alexander Hamilton to Jeremiah Wadsworth, June 16, 1797, in ibid. 21:112–113, which may be referring to Ann Lytton Venton or perhaps to the other Lyttons who helped him out.

[17] At this time, Thomas Dipnall lived at No. 56 Compagniets Gade (Company’s Street) and also owned No. 53, which he rented to Ann Lytton Venton. Working through the matrikels, it appears that Ann Lytton Venton lived in the same house that the Hamiltons had lived in a few years earlier, but one cannot be certain since the numbers and sometimes the order of properties changes with each matrikel.

Copyright

© Posted on September 9, 2021, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.