Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

As noted last week, after spending nearly eight months in prison for “fornication,” Rachel Faucett Lavien, the future mother of Alexander Hamilton, was “freed…from jail and lawsuit” in May 1750 upon her husband John Lavien’s request because he thought “that everything would change to the better and that she, as a wedded wife, change her unholy way of life and…live with him.” Despite her husband’s expectations, Rachel left the island of St. Croix by year’s end.

Where did Rachel go after her release from prison but before leaving St. Croix?

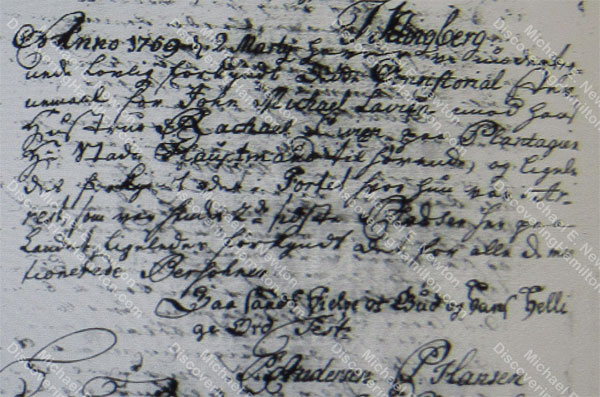

1759 Divorce Summons

Also noted last week, John Michael Lavien filed for divorce from his wife Rachel Faucett in February 1759.

As part of the proceedings, a “consistorial summons for John Michael Lavien against his wife Rachael Lavien” was proclaimed on March 2, 1759, “on the plantation owned by the Town Captain, and also proclaimed in the Fort, where she was in jail, which were her two last places of residence.”

It is thus clear that one of Rachel’s “last places of residence” was “on the plantation owned by the Town Captain.”

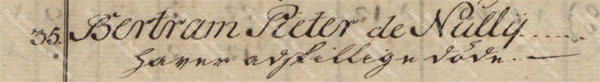

Bertram Pieter de Nully

Accordingly, Hamilton biographers have reported that Rachel Faucett Lavien went to live with Bertram Pieter de Nully on his plantation after her release from prison.

H. U. Ramsing, who discovered the above record and first wrote about it in 1939, explained, “Rachael Lavien was summoned on her last places of residence in 1750, namely the prison in Christiansvaern Fort and on the plantation of Town Captain Bertrand Pieter de Nully, Cathrines Rest in Kompagniets Kvarter (The Company’s Quarter).”[1]

Subsequent biographers have since stated, as implied by Ramsing, that Rachel went to live with Bertram Pieter de Nully at his Catharine’s Rest plantation. For example, Broadus Mitchell in 1957 explained, “Though the Town Captain’s (Bertram Pieter de Nully’s) plantation (‘Catharine’s Rest’ in Company’s Quarter) was mentioned before the Fort, it may be that Rachael went there after she was released from jail. Possibly De Nully interceded for her. Her mother may have been living on De Nully’s plantation at the time.”[2] Similarly, James T. Flexner wrote that Rachel, after her release from prison, “fled to the mansion of the town captain, Bertram Peter de Nully.”[3] Willard Sterne Randall noted that Rachel was “released to the custody of the island’s highest ranking officer” and “went to live with him on his own plantation.”[4] Ron Chernow stated that “after Rachel left the fort, she spent a week with her mother, who was living with one of St. Croix’s overlords, Town Captain Bertram Pieter de Nully.”[5]

Thus, based on the text of the divorce proclamation, Hamilton biographers explain that Rachel was released from prison and then went to live “with” Bertram Pieter de Nully on his plantation.

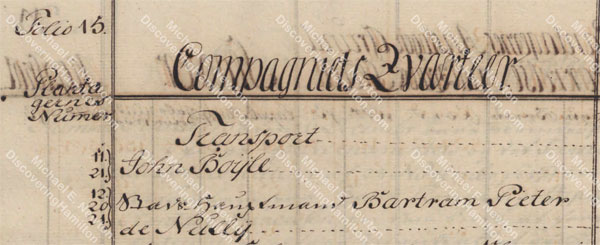

The Plantations Owned by Town Captain Bertram Pieter de Nully in 1759

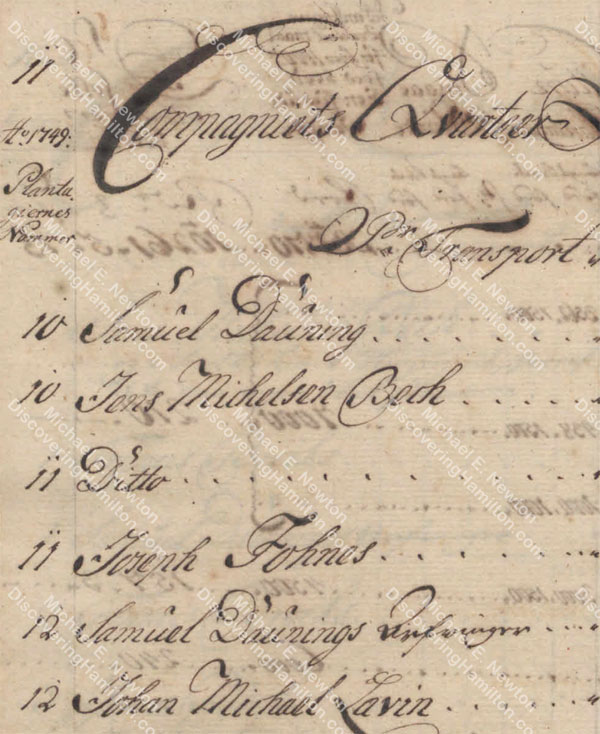

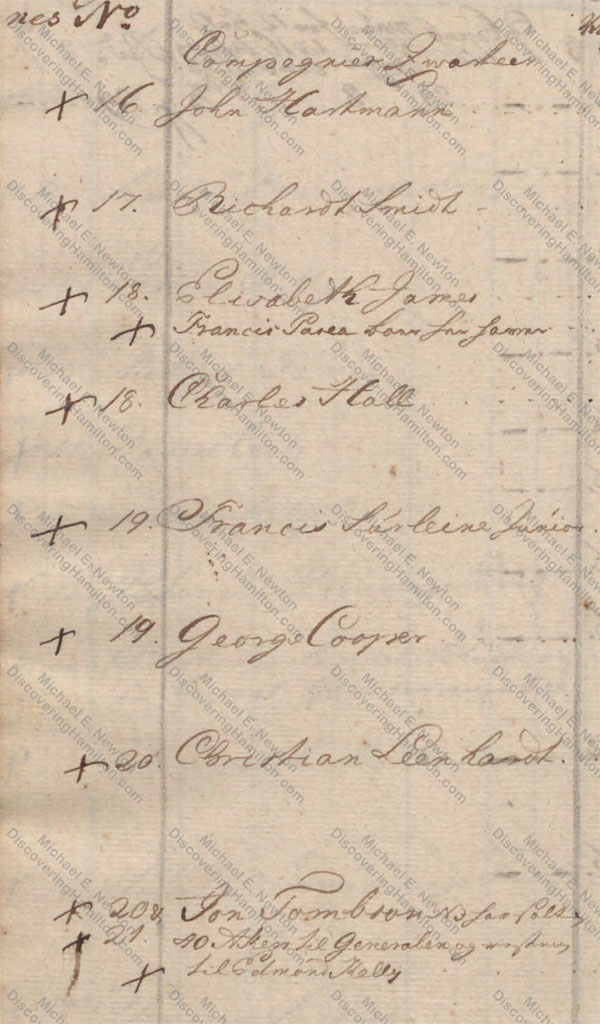

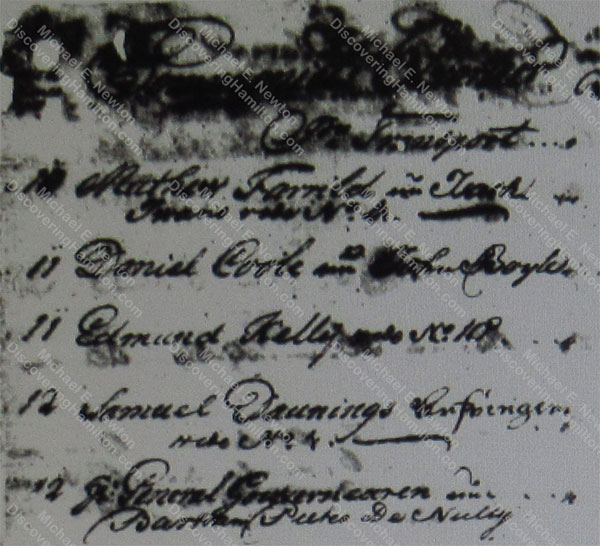

When the divorce summons was proclaimed in March 1759 “on the plantation owned by the Town Captain,” Town Captain Bertram Pieter de Nully owned a number of plantations, including Nos. 12, 20, and 21 Company’s Quarter along with No. 35 Queen’s Quarter. (The Catharine’s Rest mentioned by Ramsing, Mitchell, etc. was the name for Nos. 12, 20, and 21 Company’s Quarter.)

No. 12 Company’s Quarter in 1745–50

It just so happens that one of the estates owned by Bertram Pieter de Nully in 1759, that is No. 12 Company’s Quarter, was owned by John Michael Lavien, husband of Rachel Faucett, from 1745 to 1750.

Thus, in proclaiming the summons in March 1759 “on the plantation owned by the Town Captain,” the court did so on Bertram Pieter de Nully’s plantation No. 12 Company’s Quarter because it had been the home of John Michael Lavien and Rachel Faucett Lavien back in the 1740s and thus was one of Rachel’s “two last places of residence.” The divorce court was not saying that Rachel had ever lived with Bertram Pieter de Nully, but rather that her previous place of residence was now owned by that gentleman.

Bertram Pieter de Nully Acquires Catharine’s Rest in Company’s Quarter

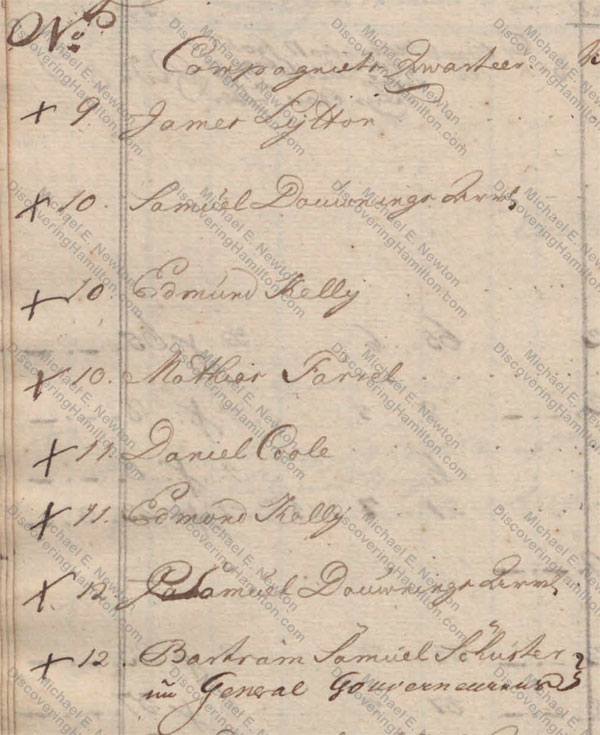

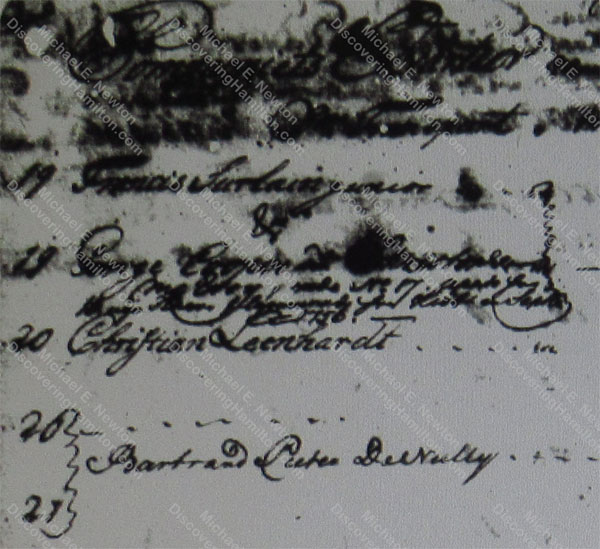

According to the matrikel from 1755, compiled in March 1756, Bertram Pieter de Nully did not yet own Nos. 12, 20, and 21 Company’s Quarter:

But the matrikel for 1756, compiled in April 1757, shows that by this time de Nully had acquired these plantations.

Thus, Bertram Pieter de Nully did not acquire Nos. 12, 20, and 21 Company’s Quarter until 1756 or early 1757. Accordingly, Rachel could not have stayed with Bertram Pieter de Nully at his Catharine’s Rest plantation back in 1750 when she was released from prison because he did not even own that property yet!

It should also be noted that the above matrikel from 1759 lists Bertram Pieter de Nully as “Stadshauptmand” or “Town Captain,” also translated or referred to as “militia commander.” But you’ll notice that in the 1756 matrikel, as in all previous matrikels, de Nully does not yet have that title. He is first listed as town captain in the 1757 matrikel. It thus appears, though one cannot be certain, that Bertram Pieter de Nully was not the Town Captain back in 1750 when Rachel was released from prison. (I have not found anyone else in the older matrikels listed as town captain and it is possible that such a position did not yet exist. Perhaps it was established after the crown took over control of the island from the Danish West India Company in 1754. More research on this front may be needed. Regardless, nothing has been found to suggest that Bertram Pieter de Nully was the town captain back in 1750, before he had purchased the plantations in Company’s Quarter and risen to prominence on St. Croix.)

Correcting An Erroneous Conclusion

Hamilton biographers are therefore incorrect in stating that Rachel went to live with Town Captain Bertram Pieter de Nully at his Catharine’s Rest plantation, or any other plantation he may have owned, after her release from prison. Rather, the divorce summons was proclaimed on de Nully’s plantation in 1759 because he had by that time acquired No. 12 Company’s Quarter, which back in the 1740s had been one of Rachel’s “two last places of residence.” Rachel did not live with Bertram Pieter de Nully after her release from prison and there was no connection between Rachel and de Nully back in 1750 or at any other time.

Where Did Rachel Faucett Go After Being Released from Prison?

While this debunks the story that Rachel had gone to live with Bertram Pieter de Nully after her release from prison, it does not tell us where Rachel went.

Unfortunately, there is no positive evidence regarding where Rachel went after being released from prison on May 4, 1750. Perhaps she went to stay with her sister, Ann Lytton, at No. 9 Company’s Quarter, later known as the Grange. Or maybe she stayed with a friend. Or she could have rented a room for a short time as she made arrangements to leave the island. Or perhaps she headed straight for the docks and took the first boat off of St. Croix. Or maybe she left St. Croix with Johan Cronenberg or possibly met up with him after they each left the island separately.

Unfortunately, despite all the new discoveries relating to Alexander Hamilton and his mother Rachel Faucett, much remains unknown and perhaps unknowable.

Support This Blog

This blog needs your support to stay online and to continue the research into the life of Alexander Hamilton, his family, friends, and colleagues.

Endnotes

[1] H. U. Ramsing, “Alexander Hamilton og hans Mødrene Slaegt.”

[2] Mitchell, Alexander Hamilton: Youth to Maturity 7–8.

[3] Flexner, The Young Hamilton 14 and 50.

[4] Randall, Alexander Hamilton: A Life 14–15.

[5] Chernow, Alexander Hamilton 12.

Copyright

© Posted on July 30, 2018, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.