Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

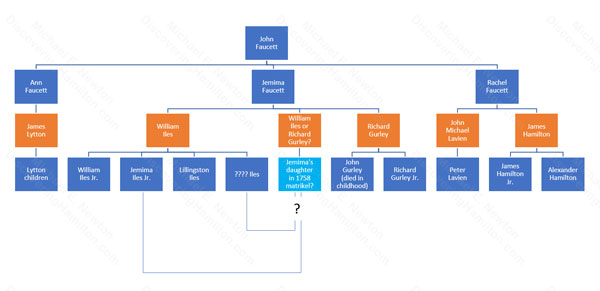

Several months ago (see part 1, part 2, and part 3), I wrote about Jemima Faucett Iles Gurley, the sister of Rachel Faucett and the aunt of Alexander Hamilton. I also introduced Jemima’s children, including Lillingston Iles, who was born in 1735 and was later found on St. Croix married, working as “some sort of builder,” and “was either illiterate or incapacitated so that he was unable to sign his name but instead made ‘his mark’ on legal documents.” We also saw how Jemima had four children with William Iles, but one child’s name had not been found in the extant records. As these children of Jemima Faucett Iles Gurley were Alexander Hamilton’s first cousins and some of them may have known Hamilton on St. Croix in the late 1760s and early 1770s, any new information about them would be of interest to us.

As a quick reminder, here is the family tree that had been included with those blog posts (people in orange are husbands of the Faucett daughters):

Lillingston Iles and Charles Iles, Masons

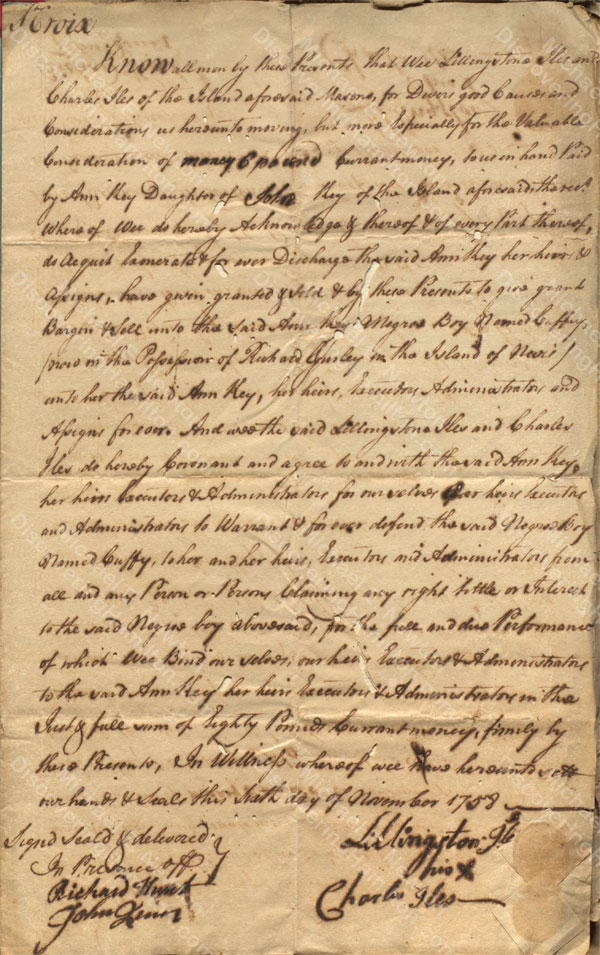

On November 6, 1758, “Lillingstone Iles and Charles Iles of the island aforesaid [St. Croix] masons” sold a “negro boy named Cuffey now in the possession of Richard Gurley in the island of Nevis.” It looks like Charles Iles signed his name and also wrote the name of Lillingston Iles, who left his mark.

Much can be learned from this one document.

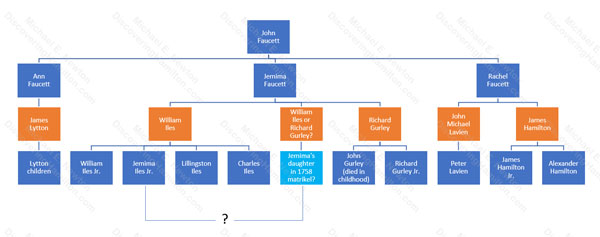

- Although not stated, one assumes that Charles Iles and Lillingston Iles were brothers. That would make Charles Iles the child of William and Jemima Iles whose name previously had not been known.

- We had seen in an earlier blog post that Lillingston Iles was “some sort of builder.” Here we see that both Lillingston and Charles Iles were masons.

- While the name is spelled Lillingstone in the text, it appears that Charles Iles wrote the name as Lillingston. As his presumed brother, Charles must have known how to spell this name. Thus, Lillingston appears to be the correct spelling.

- We had seen in an earlier blog post that Lillingston “was either illiterate or incapacitated so that he was unable to sign his name but instead made ‘his mark’ on legal documents.” This new document confirms that conclusion. As Lillingston Iles appears to have been working as a mason at this time and the two documents were signed more than a decade apart, it seems more likely that he was illiterate rather than incapacitated.

- It will be recalled from an earlier blog post that after her first husband’s death, Jemima Faucett Iles had married a man named Richard Gurley and with him had a son also named Richard Gurley. As Richard Gurley Sr. apparently died prior to 1758, the Richard Gurley who had possession of the slave owned by Lillingston and Charles Iles must have been their half-brother Richard Gurley Jr. This document shows that despite having different fathers and living on different islands, the half-brothers stayed in touch with each other and either lent or rented slaves to each other.

With the discovery of Charles Iles, the Faucett family tree can be updated (people in orange are husbands of the Faucett daughters):

To Be Continued?

While I have found Charles Iles in a handful of other records from St. Croix, they all date from around this same time period, i.e., circa 1758–1759, and these records tell us nothing about him or his life. I have not conducted an exhaustive search, but my previous investigations and additional cursory searches through St. Croix’s matrikels (census, land, and tax registers), church registers, and probate records have yielded nothing so far. The failure to find additional information suggests that Charles Iles, like his brother Lillingston, was not a man of prominence and owned no taxable property, i.e., land or slaves not rented to others. Accordingly, little if anything more may be learned about these brothers, at least one of whom was on St. Croix alongside Alexander Hamilton.[1]

Endnotes

[1] Lillingston Iles was on St. Croix in 1769.

Copyright

© Posted on November 19, 2018, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.