Much of the information in this blog (and in all previous Hamilton bios) has been updated, expanded, or even corrected in Michael E. Newton's new book Discovering Hamilton. Please check that book before using or repeating any information you read here on this blog (or that you read in previous Hamilton biographies).

Nearly all Hamilton biographers write not just about Alexander Hamilton’s mother, Rachel Faucett, but also of her sister, Ann Faucett. Rachel Faucett married John Michael Lavien, left him, established a relationship with James Hamilton, and famously gave birth to Alexander Hamilton. Meanwhile, Ann Faucett married the wealthy James Lytton, became leaders of their community, and supported both Rachel Faucett and Alexander Hamilton on St. Croix.

While these two sisters are relatively well known, John Faucett of Nevis fathered many children in addition to Ann and Rachel. (John Faucett may have had more than one wife, so to keep it simple I am simply writing about him as the father and ignoring for the purpose of this post any discussion about who was the mother of the various children.) A number of the Faucett children died in childhood and appear in the burial records of St. George’s Parish, Nevis, where the Faucetts lived, but several others simply disappear from the extant records. Without explicitly saying so, it was assumed that these other children probably died young. Although no record of their death has been found, the burial records of St. George’s Parish, Nevis, are incomplete, as are those of St. Croix. Historians simply forgot about these children, assuming that any records of their life or death are lost forever.

Thankfully, the above assumptions were without foundation. At least one other child of John Faucett has now been identified, and her story is worth telling because it is an interesting one.

The Birth of Jemima Faucett

The earliest record of a Jemima Faucett is her marriage in April 1730 (which I’ll write more about soon). Based on her wedding date, one assumes that Jemima was born towards the end of the first decade of the 18th century or in the early 1710s.

Other evidence supports this assumption.

In March 1708, John Faucett lived on Nevis with two white females, presumably a wife and a daughter.[1] As the abovementioned Ann Faucett married James Lytton sometime in the 1720s, which was before Jemima got married, and had a son with him prior to April 15, 1730,[2] one assumes that Ann was older than Jemima and that the second female living with John Faucett in 1708 was Ann rather than Jemima.

The extant baptismal records of St. George’s Parish, Nevis, where the Faucetts lived, start in May 1716.[3] Since Jemima does not appear in these records, one assumes she was born prior to that date.

It is thus reasonable and logical to assume that Jemima Faucett was born to John Faucett between March 1708 and April 1716.

Note

At this point I’d like to point out that no positive evidence has yet been found to prove that Jemima Faucett was the daughter of John Faucett. Nevertheless, having the same last name in the same location at the same time with no other known Faucetts there makes this likely. Moreover, later interactions between Jemima Faucett and other members of the family create a near certainty that she was John Faucett’s daughter.

The Marriage of Jemima Faucett to William Iles

On April 19, 1730, Jemima Faucett married William Iles in St. George’s Parish, Nevis.[4]

Children Born to William and Jemima Iles

Nearly a year after their wedding, on April 15, 1731, William and Jemima Iles baptized a son and named him William, making him William Iles Jr.[5]

The next offspring of William and Jemima Iles was a daughter, who they baptized on September 16, 1733, and named Jemima like her mother.[6]

Next, on April 9, 1735, William and Jemima Iles baptized a son and named him Lillingston.[7]

Interestingly, John and Mary Faucett a few years earlier had given birth to a son, who they baptized and named Lillingston on July 19, 1731.[8] This Lillingston had passed away and was buried on March 2, 1735.[9] It cannot be a coincidence that William and Jemima Iles named their son Lillingston just a month after Lillingston Faucett, the son of John and Mary Faucett, had passed away. One assumes that Lillingston Iles was named after the recently deceased Lillingston Faucett. This further solidifies the connection between John Faucett and Jemima Faucett Iles and supports the belief that they were father and daughter.

In addition to the above three children—William, Jemima, and Lillingston—a fourth was born to William and Jemima Iles prior to June 1739, as will be seen below. As there is a gap in the records of St. George’s Parish, Nevis, from March 1737 to March 1738,[10] one assumes that this fourth child was born during this timeframe.

The Death of William Iles and Jemima’s Financial Troubles

William Iles died sometime before June 1739. His burial does not appear in the records of St. George’s Parish, Nevis, and it may have occurred during the gap in the church records between March 1737 and March 1738.

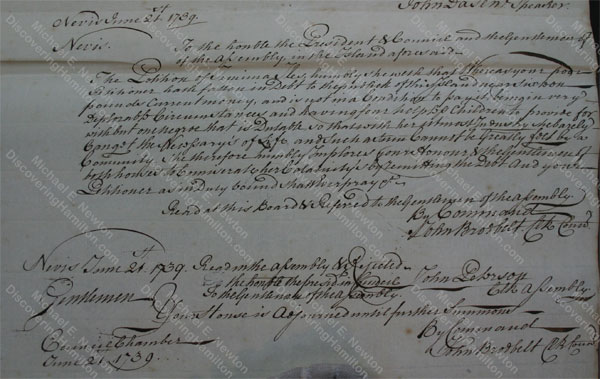

By 1739, Jemima was “in debt to the public of this island [Nevis] near sixteen pounds current money” and was “not in a condition to pay it, being in very deplorable circumstances and having four helpless children to provide for.” Despite her debt being a mere sixteen West Indian pounds or about £9 sterling, her parents were apparently unable or unwilling to help her (they would separate the following year), and she petitioned the Assembly of Nevis in June 1739 to have her debts remitted. The Assembly rejected her request.

Nevis June 21st 1739.

Nevis

To the honorable the President & Council and the Gentlemen of the Assembly in the Island aforesaid.

The petition of Jemima Iles, humbly sheweth that whereas your poor petitioner hath fallen in debt to the publick of this Island near Sixteen pounds current money, and is not in a condition to pay it being in very deplorable circumstances and having four helpless children to provide for with but one negroe that is dutable, so that with her utmost industry she barely can get the necessaries of life and such a sum cannot be greatly lost by a community. She therefore humbly implores your honour & the gentlemen of both houses to commiserate her calamities by remitting the debt. And your petitioner as in duty bound shall ever pray etc.

Read at this Board & Referred to the Gentlemen of the assembly.

By Command

John Brodbelt

Nevis June 21st 1739. Read in the assembly & rejected.

* I would like to thank Susan Moore for photographing at my request the above document within the collections of the U.K. National Archives.

To be continued…

Support This Blog

This blog needs your support to continue sharing with you the latest new discoveries in the life of Alexander Hamilton, his family, friends, and colleagues.

Endnotes

[2] Newton, Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years 9 and 513. (I will write about this in more detail in an upcoming blog post and/or book.)

Copyright

© Posted on August 20, 2018, by Michael E. Newton. Please cite this blog post when writing about these new discoveries.

Your posts about the matriarchal lines in Hamilton’s life are intriguing. In today’s you have what I believe is a typo with her marriage being in April 1930. Perhaps you intended 1730?

Also, can you enlighten me about at what point in Hamilton’s life, his biological father abandoned the family and at what points Hamilton and his father had further contact? Thanks.

Thank you Phil for your comments and questions.

Thanks for spotting the typo. Corrected!

I wrote about James Hamilton’s departure and later life at https://discoveringhamilton.com/james-hamilton-life-st-croix/ and https://discoveringhamilton.com/james-hamilton-1766-to-1799/ Be sure to also see https://discoveringhamilton.com/james-hamilton-sailor-st-croix-legal-dispute/ which give new light to James Hamilton’s circumstances, with numerous implications for his (and his son’s) biography.

The only extant letter between Alexander Hamilton and his father is https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-14-02-0369 Alexander Hamilton, however, does refer to other correspondence with his father, which have been lost.